Lawrence Gordon Clark, with one of his monsters from The Ash Tree.

Y’all ever see that movie The Signalman? About the British railwayman who sees a ghost? It’s part of a series the BBC did from 1971-1978, called A Ghost Story for Christmas. All but a handful of these films were adaptations of M. R. James stories, and all but one were directed by Lawrence Gordon Clark, who’s directed dozens of programs and telefilms for British television from the 1970s to his retirement in the early 2000s.

Mr. Clark wrote a book called The Christmas Ghost Stories of Lawrence Gordon Clark, a collection of the original M. R. James and Charles Dickens source material alongside recollections of the productions. He also has a short story collection, Telling Stories, due out soon.

Mr. Clark was kind enough to speak to me about M. R. James, Alfred Hitchcock, and his long and fascinating career:

I’d love to talk about your book Telling Stories, but I can’t seem to get a copy anywhere!

Telling Stories is a collection of short stories that Abelard wanted to get together, but they took so long I didn’t sign with them. As far as I know, they put out a cover on the net, but didn’t get any further. Simon Marshall-Jones at Spectral Press has expressed an interest in publishing a collection of my short stories, which Tony Earnshaw who produced The Christmas Ghost Stories of Lawrence Gordon Clark is editing.

Harry’s Game (1982)

You’ve mentioned that Harry’s Game is your favorite of your own works. I haven’t seen it.

Harry’s Game is a great thriller, but also a profound insight into the tragedy of Northern Ireland’s sectarian divide, which continues to this day. Gerald Seymour, the writer, had been ITN’s News at Ten reporter there, so he really knew his stuff. Gerald and I went to Belfast on a recce the weekend that Bobby Sands, the IRA hunger striker, died, and the city went up in smoke.

We were driven round by a young taxi driver of obvious Republican sympathies, and when I asked him whether it would be safe to bring an English film crew over to film, he told us to leave a script in the back of his cab. A few days later, when he was driving us to the airport, he handed it back and said it would be ok to film there. This was the only ‘permission’ that we got. I don’t think today’s Health and Safety environment would have let us go ahead.

We shot the film in Leeds where the rundown red brick Victorian terraces were a dead ringer for Belfast, and finished with three weeks in Belfast with a skeleton crew and the main actors.

I made the film for Yorkshire Television, which was headed up by Paul Fox, who had moved from the BBC where he had been Controller of BBC 1 and had given the go ahead for my ghost stories. Paul is one of the great figures of British television, and it was largely due to his determination that Harry’s Game was made at all, as there was considerable opposition to what some regarded as its too even-handed approach to the IRA.

I am particularly proud of the film because I think we achieved a realism not only about the situation in Northern Ireland but also the problems of being a soldier there. I have some experience with that, as I did my two years national service in the British army in Malaya when it was still active. When we were filming in Belfast, a squad of soldiers appeared round the corner and a not very friendly corporal asked me what the hell I thought I was doing there and, stuck for a word, I said we were making a drama. He said ‘there’s enough fucking drama here without adding you lot to the mix.’ I had every sympathy with him.

A few years later, I met a young soldier on a train, and he told me that the army showed Harry’s Game to soldiers going to Northern Ireland to show them what it was like to serve there. I have never had such an accolade for any of my other films.

All I know of it is that Clannad theme song.

We showed the finished film to Clannad and they came up with the famous theme. The late Keith Morgan, who was head of music at YTV, suggested them.

What I do know you for is your Christmas Ghost Series, of course. What attracts you to ghost stories?

Ghost stories were a tradition in my family. Dad used to read M.R. James to us as children. I was an avid movie-goer and loved Hitchcock’s films. His interviews with Francois Truffaut, and Karel Reisz’s Technique of Film Editing, were my bibles.

The Stalls of Barchester (1971)

The Stalls of Barchester was your first film and, according to IMDb, your first production work at all. Was it difficult to get the network’s trust as a first-time director?

I worked as an assistant film editor at the BBC and then went on to direct documentaries for them. It was a much freer environment in the Corporation then, and good ideas were easier to get funded. As far as I can remember, they weren’t yet cursed by a Development department. Anyway, I was desperate to make drama films, and I thought that the Christmas Ghost Story was a good idea for television, so I sent up a copy of M.R. James’s Ghost Stories with a marker on The Stalls of Barchester to Paul Fox, who was then Controller BBC 1, and suggested I make it for him. To my amazement and considerable alarm, he said yes, and I was left with a ghost story to write, produce, and direct for next Christmas, in between my regular duties as a documentary maker. ‘Bliss was it in that morn to be alive…’ Any young filmmaker who’s going off to make a film with complete freedom and a great cast and crew will know the joy I felt.

I had the incomparable Robert Hardy to play the lead, and a wonderful supporting cast. John McGlashan, the lighting cameraman, and Dick Manton, the sound recordist, stayed with me for the next four films, and their contribution to the series was every bit as great as mine. Martin Hoyle, who is now a distinguished theatre critic, trebled up as production manager, first assistant, and most memorably as the verger in the cathedral.

I storyboarded the entire film after I had chosen the location at Norwich Cathedral. I think that storyboarding films is a very good idea because, while you don’t have to stick to them, you can work the film out before you’re under the stress of shooting.

The series involves others from Dickens to the present day, but really seems to revolve around M.R. James. Why the emphasis on him?

M.R. James was a distinguished historical scholar who wrote ghost stories to be read to his academic friends. One of his most important academic achievements was the cataloging of the medieval manuscripts at the Fitzwilliam museum in Cambridge. The illuminations or illustrations of these volumes are full of images of hellfire and demons torturing the damned, so you don’t have to go any further to see where he got his spooks from, or indeed his caustic—some would say realistic—sense of the evil that exists in the world. This would have been reinforced in later years by the very graphic results of man’s evil that he witnessed in the military hospital tent that was erected close by his college to tend the wounded from the trenches of the First World War.

James has a genius for imbuing objects, usually from the past, with implacable malignity: the bronze whistle in Whistle and I’ll Come to You, the Saxon Crown in A Warning to the Curious, the runes in Casting the Runes. Hitchcock claimed that his MacGuffin could be something or nothing so long as people are prepared to kill for it, and perhaps that’s why some of the Master’s films are compelling but fundamentally empty constructs. James shared his sense of evil, but his objects are truly frightening because they resonate with our deepest and oldest fears, born when our furthest ancestors crouched at night by the camp fire trembling at the threats that the surrounding darkness held. A whistle blown could summon a demon or a mighty wind; a crown is buried to protect the coast from invasion, and it has its guardian that will punish anyone who touches it.

James has a genius for combining genuine history and folklore with the supernatural and so making it more frightening and believable. Count Magnus, his prototype Dracula, takes the Black Pilgrimage to Chorazin ‘to salute the Prince of the Air and acquire a Companion who will help him overcome his enemies’. The Black Pilgrimage was certainly James invention, but his scholarship would have told him that Chorazin is cursed in the New Testament (“Woe unto thee Chorazin”) and regarded by early Christians as the birth place of the Antichrist.

The other great quality James possesses is his ability to evoke English countryside, towns and villages, particularly on the eastern seaboard. Even today, you can find some of the places he writes about virtually unchanged, and finding locations was one of the most important and enjoyable parts of making these films.

The series was, they say, inspired by a ’68 production of Whistle and I’ll Come to You, which you were not involved in. Did you see this production when it aired?

I didn’t see Jonathan Miller’s Whistle until years after I’d made my ghost stories. This was a deliberate choice.

A Warning to the Curious (1972)

You made a career adapting very literary stories—things that, on the surface, seem hard to metamorphose into film. I like Barchester very much, but to me, the second film in the series, A Warning to the Curious, is where you really came into your own. It’s also probably the most changed from its source material. Was this one particularly challenging to adapt?

After the success of The Stalls of Barchester, I was given free reign to make this film, and a slightly larger budget, so we could afford 18 days to shoot it, which was really great. Again, we were unencumbered by any executive supervision, and I could make the film without interference of any kind. It took me a week of driving round Norfolk and Suffolk until I found the right locations and adjusted the script accordingly. I took the liberty of starting the film with the murder of the first archeologist, which James only hints at, because I wanted to show the audience that Paxton was under threat from the start, and added the scene with the antique dealer and his doll because it has always intrigued me that one of our favorite nursery rhymes, London Bridge is Falling Down, is really about virgin sacrifice to create a guardian of the bridge, and the crown in our film had a similar protector. I also made Paxton a victim of the Depression because it made him needier and more interesting than James’ rather vapid young man. It let me cast Peter Vaughan, who I’d always wanted to work with and utilize his driven, neurotic energy. Peter had just come from playing the homicidal farmer in Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs, so he was well primed for the part.

We filmed at Holkham Gap in North Norfolk in late February. It was consistently fine cold weather, with a slight winter haze which gave exactly the right depth and sense of mystery to the limitless vistas of the shoreline there.

I tried to make Warning to the Curious as, essentially, a silent film, with the tension building slowly throughout the visual images—Paxton’s spade strapped to his suitcase when he arrives on the train, the cutthroat razor laid along the name in the prayer book, the distant dark figure watching him wherever he goes and, above all, the great open spaces in which he stands vulnerable and alone, and then suddenly, the claustrophobia of the dark hotel room where he is shut in with the demon that’s scratching at his suitcase to get the crown.

How do you see television as a medium? Is it very different from film? Is it more challenging to sustain mood with ad breaks and a small screen?

As Hitch says, people don’t tell the story when they speak—they’re usually talking banalities or concealing what they’re feeling, and it’s the difference between what they say and what the camera tells you that gives true cinematic tension. Unfortunately, most television drama in England is irretrievably dialogue driven. It may be good, but it isn’t cinema.

Lost Hearts (1973)

Lost Hearts is one of creepiest of the series, and the gliding, taloned ghost children look to have anticipated, if not inspired, everything from Salem’s Lot to Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Where did that image come from?

The ghostly children are taken directly from James’s description.

Lost Hearts has been adapted several other times—once as the Mario Caiano film Nightmare Castle and once as an ITV TV film—what do you think of those?

I have never seen another version of the story. If I know about someone else’s work, I deliberately ignore it, because I don’t want it to influence my work. The story is enough to work on.

There’s a shot in Lost Hearts when the ghost walks into the boy’s bedroom to get his hurdy-gurdy which looks like it’s lit with a single handheld light—probably one of the only shots in the series to employ non-naturalist lighting. Your films are clearly carefully structured, but this image feels almost spontaneous. What was pre-production like on these films, and what kind of equipment were you working with?

Ghosts are not naturalistic, so you light them to be as frightening as you can. I storyboarded nearly the whole film but there are always times when you change your mind when shooting. The opening shot was meant to show the coach coming out of the dawn with the rising sun behind it and I found a road that ran from East to West. But when we arrived for the dawn, there was a thick mist, so we got the coach emerging out of the mist with its lanterns burning, which was probably better than my original concept. We didn’t have David Lean type budgets to wait for days till the light was perfect. We filmed in autumn, which is a good time in the English countryside—plenty of low light, golden trees, and dew-covered cobwebs on the grass. Joseph O’Connor, who played Mr. Abney, and I decided to model him on Dr. Caligari in Murnau’s great movie. (Have you read Sigfried Krakaurer’s book From Caligari to Hitler? It’s one of the great books on film and histories of how the German psyche allowed the rise of Nazism.) Anyway, the children were great in that film. I love working with children in drama because they understand the fun and manipulation of make-believe. In this case, it was scaring people, and they love doing that.

The Treasure of Abbot Thomas (1974)

After that came The Treasure of Abbot Thomas, which starts out very dark, but it starts out with an almost adventurous spirit. Do you feel like you approached it differently than some of the others?

We had a lovely script from John Bowen, which took some liberties with the story—which made it for the better I think—and Michael Bryant’s performance was pitch-perfect like Robert Hardy’s in Barchester. I’ve had great luck with my actors over the years, and the way Michael showed the intellectual arrogance of Somerton and his struggle to hide his lust for treasure was a delight. It’s really quite a funny story until it gets nasty, although the threat is always there. James has a mordant sense of humour, and it’s good to translate that into cinematic terms when you can. I’d always wanted to do a medium scene, and John came up with a beauty. I’d did another one which I’m quite proud of in a film called Prophecy in my Chiller series for Yorkshire television.

It could not have been easy filming in that church.

Welles Cathedral where we filmed Abbot Thomas is one of the most beautiful of the English cathedrals. Like Norwich, where we did Barchester, it has a marvelous library above the cloisters. Great for atmospheric tracking shots leading the audience into the story. We had no problems filming there. Our only problem was getting permission to film, as Pasolini had filmed an orgy there the year before and the Dean had nearly been sacked.

John MacGlashan, the lighting cameraman, did some of his best work on that film, and Geoffrey Burgoyne’s music was outstanding. This was the first time we had a score.

The Ash Tree (1975)

In your book you say The Ash Tree didn’t do the story justice because, with what we know of the witch trials, you couldn’t believe Mrs. Mothersole as a villain. I’d like to hear more about that—was this a realization after the fact, or a challenge during filming?

It was a realization from the start. We know so much about the hysteria of the witch trials and the ignorance and downright evil that fueled them that it was well-nigh impossible to portray her as James intended. Although, even he makes her a complicated character, hinting that she was popular with local farmers and the pagan fertility aspects that this implies. Frankly, I don’t think the script quite did justice to the story, and maybe someone else should have a go at it.

The Ash Tree feels like the darkest of the series, like its’ beset on all sides by ghosts, yet it feels like there are more day-lit exteriors than in almost any other. How did you create so much atmosphere over so many films without invoking the more obvious ‘tricks’ of film horror?

It’s very kind of you to say so. I don’t really know except that each film poses its own problem, and the director should think of himself as a storyteller who has to hold his audience in the palm of his hand. Film is a unique visual medium and the camera should, where possible, tell the story. A lot of writers don’t understand this, and ideally the director should be the writer. In the factory atmosphere of most modern television, this is impossible apparently.

How did you make the monsters at the end of The Ash Tree?

We did audition a real Venezuelan bird-eating spider for the part, but it was too temperamental.

They were created by the BBC’s special effects department, by the same man who did Monty Python’s stuff. I’ve forgotten his name, unforgivably, but you could find it easily enough.

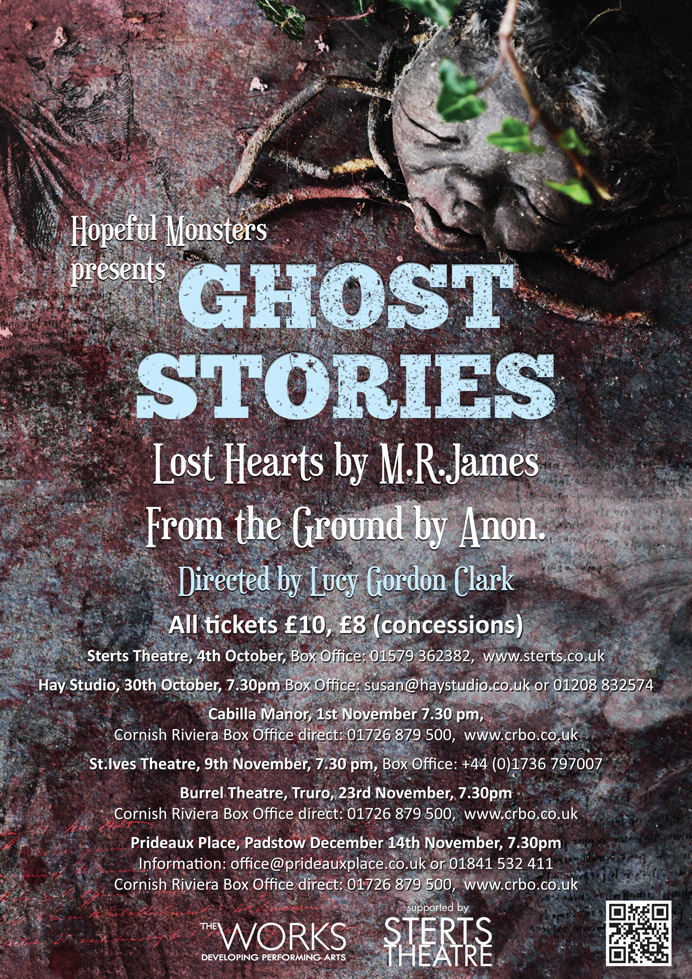

I’ll send you a picture of one I took for a theatrical tour that my daughter, Lucy, who is a very fine director, did.

The Signalman (1976)

Of the series, The Signalman seems to have exploded in popularity beyond the rest.

I don’t think this film got markedly higher ratings than the others, but we had a great location and Charles Dickens and Denholm Eliot to help us.

The Signalman is the series’ first non-M.R. James adaptation. How is Dickens’ style of horror different from James?

As I say in the book, this film is about fate rather than ghosts, and Dickens’ prophetic insight into the iron straight jacket industrial man was creating for himself. You probably know he was involved in a train accident himself.

I don’t think I can really add anything more to what I said in the book.

Stigma (1977)

Your last film in the series, Stigma, is the first to be set in the present-day and not based on a classic story. How do you feel it’s aged compared to the others?

It’s aged because of those terrible flares!

I didn’t enjoy making this film because I didn’t get the crew I wanted—the BBC had cut the budget and I wanted to make Count Magnus by M.R. James but they wouldn’t put up the money for it, which I felt was pretty shortsighted considering the success we’d had with the series. I’d left them that year to make some films for Yorkshire Television, so that was the last one I did.

That said, Clive Exton gave us a very good script, Kate Binchy was marvelous, and the film was quite effective.

What was your vision for Count Magnus?

It’s a difficult story because the main character is so stupidly rash and you know that there’s no escape for him from the start. I’m most intrigued by the Black Pilgrimage to Chorazin that the evil Count makes, and have included that in a story of mine called The Ring, which is a tribute to both Count Magnus and Casting the Runes. Hopefully, Simon is going to publish some of my short stories, and I hope you get to read them.

The series was revived a few times, but none of the films made in the 2000s hooked me.

There was one good one. A View from a Hill. Very sinister.

Jamaica Inn (1983)

You mentioned your impression of Hitchcock’s films as “compelling but fundamentally empty constructs.” My mind immediately jumps to your Jamaica Inn, which takes a totally different tack than his version.

I said “some” of Hitchcock’s films, and that was rather arrogant. He is a master to whom I owe most of my understanding of film.

Jamaica Inn has more color than the ghost stories. Who was the DP on that? There’s no one listed on IMDb.

Brian Morgan was the DP and he did a great job. I am very proud of the wrecking scenes, which we shot on Polzeath beach, N Cornwall, in a force 8 gale. The sailing for them was done by a friend of mine, Robin Cecil-Wright, and the crew of his square-rigger, the Marquesa, that was subsequently to sink in a tall ships race off Bermuda.

I think it was not altogether successful, nor as frightening as it should have been. Jane Seymour and Patrick McGoohan were great fun to work with, both being very intelligent as well as fine actors. I’m only sorry that I couldn’t find a central cohesive tension to the film.

Do you think it’s something central to the story itself? Hitchcock clearly struggled with it too. It’s one of his only movies that feels longer than it is.

I think so. It’s a bit of a potboiler, really. Not one of du Maurier’s best books, and it is a bit long. I had some great character actors though, including Tony Rohr, who played the IRA chief in Harry’s Game, among a wonderful bunch of scoundrels at the inn.

I haven’t looked at the film for years. Does it still get broadcast? The last time I watched it was in a hotel in Hong Kong when I was flying to Australia, and it had Chinese subtitles down the side.

Speaking of Australia, have you seen my Captain James Cook, aka, The Wind and the Stars?

I haven’t.

I made it in 1986 for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation in Tahiti and Australia. We had a pretty tight budget, but a wonderful script, The Bounty—which was built for the Mel Gibson Mutiny on the Bounty—and a towering performance by Keith Michel as Cook. Because it was a co-production with Canal+, we had some great European actors, including Fernando Rey of The French Connection playing an English admiral.

It’s one of my favourite works, though I could have done with more money and time. Cook was one of the great explorers, a genius navigator and a great man and I was really lucky to get to make the film.

I love Fernando Rey, so I’ll have to keep an eye out.

Prophecy (1995)

I watched your Chiller episode Prophecy last night. It was very creepy. Felt like it was paving the way for Final Destination, in a way. Your contemporary horror movies always seen to have a different feel than your period pieces—somewhat more sexual and visceral. Any thoughts on that?

I think that’s because James was almost studiedly averse to sexuality, and if you adapt his stories, you have to respect that. I think he says somewhere that sex has no place in a ghost story—and certainly, the repressed nature of his characters make them prone to haunting—but I personally don’t believe this generalization to be true.

I’m rather proud of Prophecy and the twist at the end. It’s a good story, and certainly has a truly evil character/ghost as it’s driving force, which James would have approved of!

Casting the Runes (1979)

Among your post-Ghost Story work, you took on M.R. James again with Casting The Runes. Just about every adaptation of this, from Night of the Demon to Drag Me to Hell to your telefilm is set in the present day. Why is that?

Casting the Runes is a timeless story and doesn’t have to rely on the Edwardian patina of the original. Tourneur’s Night of the Demon has a wonderfully bleak feel to it in spite of the slightly absurd monster. And I like to think we got a similar quality out of snow-bound Leeds.

Karswell is one of the great villains. I imagine him to have been a magician in some great European traveling circus who sold his soul in order to perform really great illusions, and is bound like Faust to eventual damnation which he can only temporally evade by diverting it to other victims. He probably spent some time in early Nazi Germany counseling Rosenberg and Himmler and other National Socialist crazies on the uses of the occult for their world domination plans before coming to England as a bogus refugee.

There could be a great film there.

He is an amazing man who has a amazing feeling for directing. I am very happy he is my grandfather he has taught me a number of things about directing and acting. So I hope you have the passion to read or watch one of his outstanding ghost stories. They may make you shiver till your hearts content but he will really appreciate it. Thank you.

Beatrice, I’m so happy you liked the interview! Your grandfather is remarkable.

Hello beatrice, i’m the assistant of the director Arouna Lipschitz, she wanted to get in contact personally with your grandfather.

Would you be so kind and contact me back on my regular email address : isabelleerrera@hotmail.com

Thank you so much for your kindness.

Hi John,

Is there a contact I can reach you directly on?

Thanks,

Tom

Hello Beatrice,

I have a friend called Joanna-Gordan-Clark who is in a care home at the moment but is expected to move into alternative accommodation. She is still of sound mind but recovering from a broken hip.

Is Laurence Gordan Clark her brother? I live 120 miles away from Joanna and I would like to help her more, I suspect she is being sedated . I am worried about her home in Cambridge as she needs to make safe her front garden and build a lift before she can return home but her attempts at contacting tradesmen have not been successful, I suspect ,due to her being in a Care Home and tradesmen thinking she is not mentally ok. I think she needs support from her family but she is very feisty and obstinate she needs love and support. Can you help?

Just had a collection of mr Clarks ghost stories for christmas, as I love M.R James and saw a few of these films growing up. Just watched warning to thw curious- wow – really tense, beautifully filmed and very scary. Your grandfather is very talented. Really looking forward to watching the rest in the run up to Christmas. Did your grandfather watch the 2013 Christmas ghost story? What did he think? All the best.

Dear Lawrence,

So lovely to meet you yesterday at Brian and Sally-Jane s.

How was it that I was totally unaware of your brilliance. How could you have hidden that from me!

Hopefully we’ll meet again.

I have given James Keith, my son, the details re Drones and Poppy.www.lightcoloursound.co.uk

Hope this all makes sense?

With many good wishes

Wendy Harvey Clark

I have noticed you don’t monetize your blog, don’t waste

your traffic, you can earn extra cash every month because you’ve got hi quality content.

If you want to know how to make extra bucks, search for: Mertiso’s tips

best adsense alternative

Hi, is anybody here interested in online working? It’s simple survey filling.

Even $10 per survey (10 minutes duration). If you are interested, send me e-mail to hansorloski[at]gmail.com