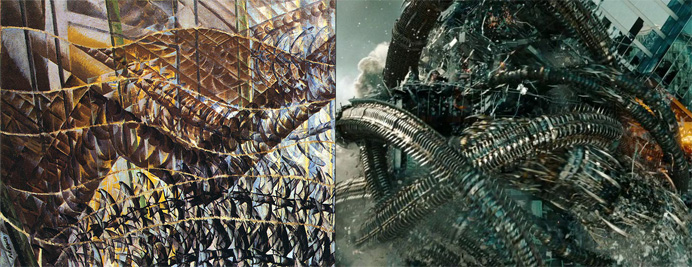

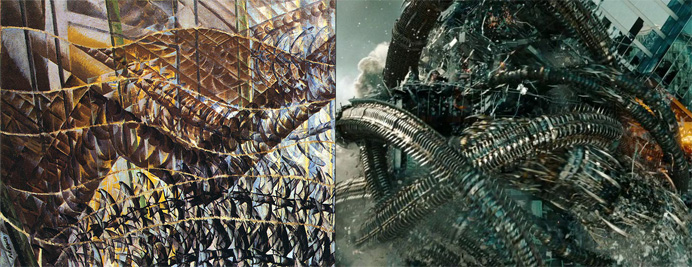

Paths of Movement + Dynamic Sequences, 1913 | Transformers: Dark of the Moon, 2011

Film, the most sensory of the arts, is probably the best-equipped to present movement. It has a unique combination of music’s temporal toolkit, painting and sculpture’s visual toolkit, literature’s narrative toolkit, and dance’s physical toolkit.

Movement is one of the great challenges of art. From The Iliad, which has been beautifully defined as a work about “the human spirit […] as modified by its relation to force,” to Debussy’s Engulfed Cathedral, a non-representational description of the vertical motion of a building sinking and rising out of the ocean, a great deal of art across all media and all eras strive to fabricate motion without actually moving the observer. And if film is the most intuitive for presenting movement, action film, with its implicit promises, is the most intuitive approach within the medium. Just as the existential novel is the story of the human spirit navigating metaphysics, action cinema, just like The Iliad, is the story of the human body navigating time and space.

Great (or at least vital) action, from Die Hard’s annihilation of architectural space (I don’t praise much about Die Hard but this is definitely a plus for it) to 300‘s development of the fluid freeze frame, refines how we process space and time. But, of course, cinema is incomplete. Motion can only be suggested, not reproduced (with the exception of awkward jerky theme park rides). You don’t really get hit when Rocky does, of course—and you don’t really jump off that building with Sergeant Riggs. That distance between reality and presentation means filmmakers must translate physical sensation into aesthetics, and hey—that’s where art lives.

Continue reading Michael Bay: Futurist