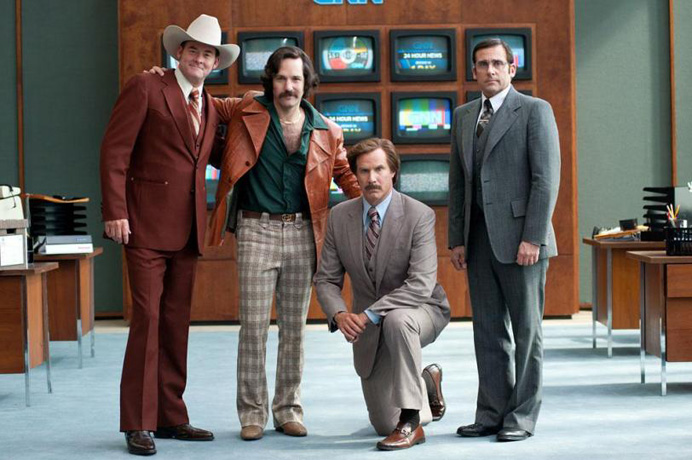

Anchorman 2: The Super-Sized R-Rated Cut (2014)

Directed by Adam McKay

Written by Will Ferrell & Adam McKay

143 min. (24 min. longer than the original cut)

We’ve all read Greg’s great review of Anchorman 2. He breaks the film down on a mechanical level, getting to the heart of it by working through its raw material: its jokes.

It’s this raw material which has been replaced in this new version.

This isn’t the first time an alternate version of a film has seen theatrical release. Exorcist II and Heaven’s Gate were notoriously pulled from theaters and recut. I remember seeing The New World in New York in 2005, and when it got a wide release a few weeks later, it was about 10 minutes shorter. But unlike these films, the reason for Anchorman 2’s recutting is not because there was something ‘wrong’ with the original—the filmmakers here simply wanted to experiment with the possibilities of cinema.

This isn’t the first recut of an Anchorman movie. Wake Up, Ron Burgundy is an alternate cut of the first Anchorman, which Greg touched on in his review (and which we saw together after acquiring it from the wonderful and unfortunately long gone Kim’s Video of Bleecker Street). It was a direct-to-DVD release, and featured many different jokes, but the main difference was its integration of a completely discarded plot that revolved around a revolutionary terrorist cell robbing banks in San Diego (which was clearly deemed unsatisfactory, and reshot as the Panda Watch section of the original film). The film tries to weave a half-assed narrative out of these scraps, using some leftover jokes as the glue.

The new version of Anchorman 2, however, is not at all different in terms of plot. In fact, beat by beat, it’s the same. If you’re someone who only half-watches movies, you’d be forgiven by some for not thinking anything was different—but you wouldn’t be forgiven by me. The fabric of Anchorman is its jokes, and now, for once, the emperor really does have new clothes.

We may lose a couple great jokes from the original cut, replaced by weaker ones, but these weaker ones often serve as necessary setup for three great new ones that couldn’t have fit in otherwise. In any case though, it’s futile to compare and rate the jokes. Instead what is important and worthy of discussion is the space these jokes occupy. By this I mean the entire philosophical concept of switching one joke for another.

What this recut of Anchorman 2 has done is reclaim realism for the cinema—realism which takes into account the infinite possibilities of how a person, in real life, can answer a question, respond to an insult, go in for a kiss, or even enunciate a word. Basically, it brings it all back to the realm of theatre. In cinema, choices are made to be ‘this’ or ‘that’—in theatre, tonight it can be this, but at the matinee tomorrow, we can try that. This mentality dictated Orson Welles’s sense of cinema: we’ll try this shot now when we premiere it at Cannes, but when we do the domestic release later, I’ll try this other shot. It’s no surprise Welles was a theatre man.

The elements of cinema are vast. There is, of course, a major mechanical element to it—the camera mechanically reproduces the images, to be manipulated later by the editor and director. But the camera is the last chance of a look at reality. I mentioned in an earlier article that the camera is more or less an idiot—it’s not really an extension of a cameraman (although the term ‘cameraman’ does imply that, like a strange bionic cyborg from a science fiction story). It’s actually just a tool used by a man. And the elements placed in front of the camera, although not always mechanical, are typically concrete elements: a painted wall, a chair, a cigarette, a pad of paper—’things’, essentially. Due to their prevalence, it is tempting to say that these things are the essence of cinema—but they are not. Amidst us being bombarded by things, it is the actor, with their movement and voice, which brings humanism to the picture—and with that, reality. It is what separates movies from a cemetery, and what gives them the life that has sustained them well as an art form for over a hundred years.

When you compound these actors with jokes, another layer of reality and humanism is added. Laughter is the easiest reaction to provoke, at least in terms of speed. Fear and dread seep in slowly, whereas humor is like a gunshot—once fired, the reaction is there. To laugh at something funny or ridiculous is knee-jerk, and of course, we can analyze ‘why’ later, but the deed is done, instantaneously. (Not that there’s anything wrong with laughter that hits you later—it’s maybe even more challenging to create a joke like this. Great examples can be seen in works such as Mr. Show and the Coen Brothers films. The Coens even summed up this concept well in Raising Arizona, by having Sam McMurray’s character label a joke a “way-homer”—because you only get it on your way home.)

The freedom that actors contain within themselves—for humor and for anything else—is obliterated by the mechanical process used to capture it. They are frozen in motion, in space, and in time. But within the editing process, freedom begins anew—one can see the limitless possibilities laid out before them. But as the film is cut, certain combinations of shots are selected, and the film dwindles down once more into something static.

The ability to look at multiple film realities, in the form of alternate cuts, brings us back, in some small way, to the freedom available to filmmakers at the very start of the process, and briefly during editing, and as such, is an important victory in the battle for supremacy between human beings and static things. We now have a more vivid idea of a movie, one that doesn’t conform to the inferior cinematic approximation of reality which we’ve previously grown accustomed to.

With both versions of the film available on Blu-Ray, we are also treated to various deleted scenes and blooper reels that could keep an amateur editor busy for months constructing new cuts of the film that appeal to them personally as individuals. You see these kinds of fan edits all the time for Star Wars and whatnot—it allows anyone with a computer to shape a film the way they feel it should be, blurring the line between audience and filmmaker. (And what better definition of filmmaker is there than an ‘audience member supreme’, i.e., a viewer with arbitrary sole judgment on what the film should be?)

For Anchorman 2 to take this approach with its core raw material—its jokes—is nothing short of revolutionary. It shows that there can be a core to a film other than its story, and also that this core doesn’t necessarily have to be present in the script, and can in fact be created in-situation while the cameras are set up and the humans and things are having their interaction. It also shows that this core doesn’t ever have to be stable—it can be ever-changing, in order to allow maximum freedom of enjoyment to both filmmaker and audience.

This film restores my faith in cinema—cinema as an open landscape, where we can tell the story of Ron Burgundy a million times, and each time can be completely different and fresh. It is nothing short of a necessary rejuvenation of art—even though on the surface it may look to some like a bunch of grown men acting like idiots.