Shortly after seeing Birdman, I happened to begin reading Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer. It was good timing as I quickly realized that both works have a strong focus on the creative process and what happens in the minds of artists. They also both share a strong disdain towards the popular works of their time. Miller writes:

“There is only one thing which interests me vitally now, and that is the recording of all which is omitted in books. Nobody, so far as I can see, is making use of those elements in the air which give direction and motivation to our lives…The age demands violence, but we are only getting aborted explosions…Passion is quickly exhausted. Men fall back on ideas, comme d’habitude. Nothing is proposed that can last more than 24 hours.”

Miller was talking about writing and politics—failed revolutions. But as I began thinking about Birdman in order to write this review, I kept thinking about that quote, and how perfectly it seems to summarize the state of film today:

“The age demands violence, but we are only getting aborted explosions.” That sounds like superhero movies to me.

“Passion is quickly exhausted.” The immediate gratification and empty calories of Man of Steel or Amazing Spider-Man.

Birdman is not a superhero movie, but it is a film about superhero movies. And about art, and passion, and the struggle for meaning, and the horrific feeling of drowning that accompanies irrelevancy.

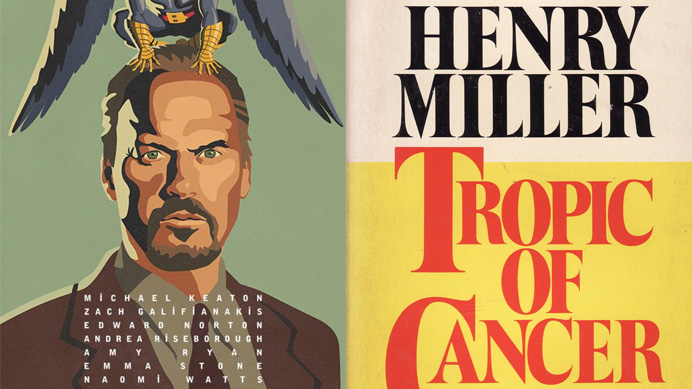

Riggan Thomson (Michael Keaton) is a washed-up actor, famous for playing the superhero Birdman in a series of movies in the 80s and 90s, who is now trying to mount a Broadway play and re-establish his career. He is directing and starring in an adaptation, which he wrote, of Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love. Unfortunately, the production begins going to hell when one of his actors becomes incapacitated two days before the first preview performance. Riggan’s producer, Jake (Zach Galifianakis) convinces him to hire famous stage actor Mike Shiner (Edward Norton) who agrees to join the production because his girlfriend, Lesley (Naomi Watts) is playing the female lead. Mike is a professional who memorizes the entire script in a day, but is also erratic, egotistical, and prone to violent outbursts.

Pressure comes down on Riggan as every preview performance turns into a disaster, often due to Mike. Meanwhile, he must deal with his recovering drug addict daughter (Emma Stone) his pregnant girlfriend (Andrea Riseborough) and the looming specter of the Birdman character he once played, whose voice haunts him—Keaton’s own, in a parody of Christian Bale’s gritty Batman voice—and drives him to lash out in fits of destruction.

At its core, Birdman is about identity. To the public, Riggan is a beloved superhero. But that isn’t enough for him—it’s too low-brow. The admiration he receives isn’t the right kind of admiration, so he launches this vanity project play in order to make something “meaningful”.

Riggan is forced to choose between the two sides of himself: the wannabe tortured artist seeking to create something powerful and moving, or the pop comic book hero he already is—“You are Birdman. The people love you. You are a god to them,” says the voice in his head. And it’s through this conflict that Birdman brings the violence our age demands.

I won’t give too much away, but there’s an important line about the significance of “spilling real blood”. Edward Norton’s character, for instance, is a method actor who demands as much realism on stage as possible (drinking real gin and requesting a real gun be pointed at him). Telling the truth on stage is what matters—that’s where blood must be spilled. Real life is secondary to creating something honest. Superhero movies don’t spill blood (they’re all rated PG-13). They’re spurts of weak passion that quickly dry up—“aborted explosions,” as Miller puts it.

Birdman is a creature that is destroying Riggan, a ghoul from his past that he can’t escape. If he accepts himself as Birdman then he compromises his soul and resigns to being a washed-up comic book character for the rest of his life. He has true passion within him that needs to be unleashed. He has to prove that he is not Birdman. But the world is stacked against him, convinced that he’s incapable of achieving anything more than pop trash.

In Tropic of Cancer, Miller writes about wanting to create what will become known as “a new Bible—The Last Book,” a work so triumphant it will shake the world of literature. Alejandro G. Iñárritu, like Miller, cuts to the heart of this type of desire. In Riggan, Iñárritu has created a character who recognizes that art is bigger than any one man. The results are slick and flashy. The spectacle of giant alien monsters and massive armies are lampooned and outdone by the spectacle of theatre and flowing camerawork. Birdman is a testament to the passion and chaos of creation. Superhero movies may buy the mansions, but they don’t achieve the highest goal of art—to let the blood pour out in front of the audience and reveal a truth.