Suicide Squad (2016) | Written and Directed by David Ayer | 123 min.

Spoilers ahead.

“On this Earth, every act is a political act.”

– Andrew Sullivan, Batman v Superman: Dawn Of Justice

In the post-9/11 era, superheroes have changed. They’ve always represented power, but the source of that power has shifted. In the early 2000s, Spider-Man struggled with the personal responsibility that came with his great power, and the X-Men struggled against a government that hated and feared them. In the mid-to-late 2000s, Christopher Nolan and David S. Goyer turned Batman into a representative of the Bush Administration—defending illegal extradition and wiretapping due to the clear and present danger of the Joker—and pitting Bruce Wayne, billionaire playboy socialite and son of privilege against Bane—a cynical proletarian revolutionary that mixes Occupy Wall Street with the Reign of Terror.

This mindset was carried into the 2010s by Goyer, now accompanied by Man Of Steel and Batman v Superman director Zack Snyder, with Ben Affleck as an older, even more grizzled Batman quoting Dick Cheney as rationale for murdering Superman: “He has the power to wipe out the entire human race, and if we believe there’s a one percent chance that he is our enemy we have to take it as an absolute certainty—and we have to destroy him.”

Of course, the largest and most profitable example is Marvel’s Cinematic Universe, beginning in 2008 and slated to carry into at least the early 2020s, which centers power under SHIELD—a vision of Homeland Security that has access to a flying base the size of an aircraft carrier—and their benevolent but shadowy leader, Nick Fury. Suicide Squad, the latest addition to the DC Extended universe, takes aim at this conception of power, casting their super-team as a corrupt mirror image of the Avengers.

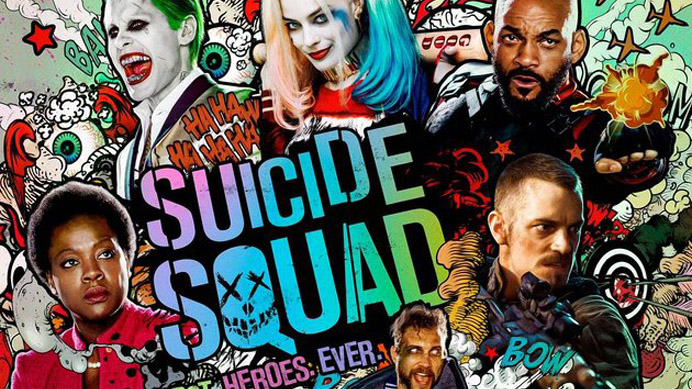

This corruption starts all the way at the top. The first two scenes, introducing Deadshot (Will Smith) and Harley Quinn (Margot Robbie) establish the power dynamics at hand. Deadshot’s back-and-forth banter with a prison guard played by Ike Barinholtz ends with the entire guard staff brutalizing him and a series of quick cuts between surveillance cameras establishing that this is a coordinated effort. The cameras are showing complete calm, but we can still hear the impacts—the Blue Shield is in full effect.

Harley Quinn’s scene, also involving Barinholtz, follows a similar trajectory: they share banter, and Harley ends up on the receiving end of horrific violence. However, while Will Smith is the victim of police brutality, Harley is force-fed, a form of torture that at once recalls the treatment of women in the suffragette movement and the treatment of inmates at Guantanamo Bay, with Barinholtz even taking a selfie with her mid-feeding. And just to add insult to injury, the scene ends with Barinholtz making a remark about her mental stability—a deeply ironic sentiment given the context.

These power dynamics are then given a direct representative in Amanda Waller (Viola Davis). Her entrance into the film is visually potent—to the strains of Sympathy For The Devil, she exits a limousine, walks past a street vendor selling Superman memorial shirts (an interesting detail that turns Superman into a super-powered Tupac) and smiles at Superman’s demise before entering a luxury restaurant. Not subtle, I know, but it works—she is immediately presented as both a representative of elite power and an opportunist to rival Richard III. Animal imagery links her to Barinholtz’ cruelty, with her leopard print bedclothes and the tiger shirt Ike Barinholtz wears in his gambling scene (a shirt that is rad as hell, by the way) linking them as predators who use their power to prey on the Suicide Squad. And, speaking of the immortal hand or eye that frames that fearful symmetry, later in the film she is framed as divine—Rick Flagg (Joel Kinnaman) calls her “the voice of God” and Harley Quinn asks if she’s the devil, to which she answers “maybe”, further cementing her position of power and moral ambiguity.

With Waller introduced, the Suicide Squad is given their own set of introductions, and these introductions place them as inversions of the Avengers, both in terms of morality and in terms of class.

The Avengers are comprised of representatives of traditional power. Captain America is, of course, nationalism—he drapes himself in the flag, yet holds himself to a different, usually higher set of ideals than his own government. Iron Man is capitalism—the means of production turned into a weaponized suit. Thor is monarchism—both in his role as a member of the Asgardian royal family and his divine role, the divine right of kings in its most blatant form. Hawkeye and Widow are government agents—their power purely political. Finally, the Hulk fills a more abstract role—the uneasy balance between the citizens and the military. Much as the United States holds the power to flatten the Earth with nuclear flame and still have enough for half the solar system, Hulk holds incredible power, and with it, is under incredible responsibility, as his ability to control his emotions is the difference between a city saved and a city destroyed.

The Suicide Squad turn these political archetypes on their head, with the Squad as the victims of power rather than its masters. Rick Flagg, the Everyman Soldier, isn’t loyal to his country so much as he is blackmailed by it, with Waller holding his girlfriend, The Enchantress (Cara Delevigne) in the palm of her hand, able to crush her heart, and his with it, at any moment.

Deadshot participates in commerce, taking in a cool two million for an assassination to the strains of Action Bronson, Mark Ronson, and Dan Auerbach’s excellent Standing In the Rain, but he’s no Tony Stark. He is not the one who controls the means of production—he is a means to be exploited, and he knows it. In the scene where Waller and Flagg decide to test if he is indeed “the man who never misses” by letting him loose at a firing range, he recognizes that he’s being sold, and the soundtrack does too, setting this product demonstration to Kanye West’s “Black Skinhead”, a song that also addresses black skill being sold as spectacle: “Middle America packed in/Came to see me in my black skin/Number one question they’re askin’/Fuck every question you askin’”. But he doesn’t fully realize just how powerless he is, making a list of demands before being shut down by Flagg.

Captain Boomerang (Jai Courtney) fills the Thor role, replacing a king with a colonial subject. Waller makes this blatant in his introduction: he came to America after cleaning out all the banks in Australia, and proceeds to clean America out the same way, going so far as to steal a $3000 watch off of a dead soldier. While the scene where he convinces Slipknot (Adam Beach) to join him in skedaddling and Slipknot dies in the attempt is taken straight from the comics, the major change Ayer makes is an important one. Casting Canadian Native actor Adam Beach in this role gives it a symbolic energy—Boomerang as the early American, Canadian, or Australian settlers exploiting the indigenous population, usually in ways that result in those indigenous peoples’ death.

Neither Harley nor Katana (Karen Fukuhara) are direct analogues to Black Widow, but Katana, despite her lacking characterization (perhaps a casualty of Suicide Squad’s contentious editing process) has the stronger case, as a government agent with a strict moral code. But her aforementioned lack of meaningful characterization prevents further analysis.

When it comes to the Hulk, the comparison isn’t quite as cut and dry. Killer Croc (Adewale Akinnuoye-Agbaje) is the aesthetic equivalent to Hulk, with both willfully setting themselves apart from society. The difference is that Hulk separates himself from society so he won’t cause them harm, but Croc separates himself from society so they won’t cause him harm. Waller says it herself: “He looked like a monster, so people treated him like a monster, so he became a monster”. But in terms of his relationship with his own power, El Diablo (a fantastic Jay Hernandez) is the clear comparison. Whereas Hulk agonizes over the responsible use of his power, Diablo has decided that there is no responsible use of his power. In particular, Diablo agonizes over the use of his power against women and children—war crime imagery not usually seen in a superhero context.

Enchantress, not a member of the Squad proper but still under the control of Waller, holds a two-pronged significance—she’s the two sides of the American military-industrial complex. In her benign self, Dr. June Moone, she seeks knowledge and progress, but as Enchantress she’s a means of espionage. Flagg, and by extension America, has a love-hate sort of relationship with her: he loves June Moone but is horrified by the Enchantress—much like the American public enjoyed the fun byproducts of the Space Race, like satellite TV, those nifty pencils that write upside down, and the 3D graphics that make up half of this and every other blockbuster, but were horrified by the existential threat that came from the development of nuclear-equipped Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles. In the scene where Waller demonstrates Enchantress’ powers to the Joint Chiefs of staff, special focus is paid to a shot in her transformation where Enchantress’s hand slips down Moone’s arm, locks fingers with hers, and flips her hand over—the technological and militaristic sides of US imperialism go hand in hand, inseparable.

As well, the Squad draws heavily from class archetypes for its character design. Harley Quinn and The Joker draw from ‘white trash’ culture, with Harley sporting an affected Brooklyn accent and Joker (Jared Leto in the most underplayed, reasonable version of The Joker in decades) mixing elements of James Franco’s performance as Alien in Spring Breakers and Ninja (of Die Antwoord)’s underrated performance in Chappie to create a persona humorist and Chapo Trap House co-host Matt Christman described as “Horny Macklemore”. Throughout the film, however, Joker gains power through costumes of power and status: the tuxedo he wears to rescue Harley, the military helicopter he rescues her with, and the SWAT getup he wears in the final scene, when he breaks through the wall of Belle Reve to break her out, her white knight in tactical armor.

El Diablo and Killer Croc draw from similarly class-stigmatized urban Latino and Black subcultures, though their individual approaches to their image provide an interesting contrast—Killer Croc is treated a certain way because of a physical condition he cannot change, whereas El Diablo actively chose to mark himself with an intricate network of tattoos. Croc is separated from society from birth, but Diablo actively separates himself from society, creating a fearsome, intimidating identity for himself as a means of showing dominance.

Boomerang is Australian, but doesn’t dress like one. He’s not wearing Steve Irwin khaki shorts or a Crocodile Dundee hat. Rather, he wears a tracksuit, which has become a cultural signifier for “lower-class white criminal” whether it’s worn by a London chav, a Russian gangster, or an Italian gangster.

Despite not being one of the criminals on the Suicide Squad, Katana’s outfit includes elements of Japanese biker gang fashion, most visibly the large bow holding her jacket shut. Again, it’s a shame she didn’t have a larger role in the final cut, as this aesthetic choice implies they may have originally had her playing a more prominent role, or at least one that involved doing something at all.

Rick Flagg and Deadshot meet in the middle. Rick Flagg typifies White America, but not the ‘criminal sort’ of White America—he’s the Real America of GOP rhetoric, a Southern soldier who makes references to Miller Time and enjoys a privilege that more lower-class criminals don’t. An American Dream of relative power.

Deadshot is an American Dream, too, but a different sort. He’s Jay-Z—a criminal hustler who loves his daugher and God, going so far as to inscribe biblical verse on his outfit. And these two American Dreams duke it out via a very particular sort of racial dichotomy—sports radio. Rick Flagg is a lunchpail, 9-to-5 soldier, with a haircut Grandpa Simpson could set his watch to, and Deadshot is a hip-hop style diva, the Cam Newton of war. This conflict is established early, with Flagg holding his status as a “real soldier” above Deadshot, denigrating him as just a mercenary, who “kills for a paycheck”. However, this dichotomy between real soldier and soldier of fortune is an illusion, proven in a scene where Deadshot, standing high as he fights off wave after wave of insect-like, Starship Troopers-esque dehumanized enemies that are explicitly shown to have been fellow soldiers, as a crowd of generic soldiers sent to accompany the Squad look on. Deadshot, the amoral killer for hire, is more of a soldier than the actual soldiers. Anthony Lane of the New Yorker cited this as an absurdity: “Some viewers, in turn, will stare in equal wonder and ask themselves, What are the chances for gun control, honestly, if this is what Hollywood—supposedly a fortress of liberal attitudes—prefers to hold aloft, these days, by way of a heroic stand?” But just look at Chris Kyle’s use of Punisher imagery in American Sniper (both his memoir and the biopic based on it)—it’s far less absurd than Lane thinks that an American soldier would venerate a killer like Deadshot.

Once the Squad’s mission goes south, this squad of the exploited engages in collective action—they go on strike, entering a nearby bar one by one instead of following Flagg’s orders. This strike is only broken when Flagg finally acknowledges Deadshot as an equal, revealing that the prison had received letters from Deadshot’s daughter and not made him aware of this fact. This act of solidarity, showing that he holds allegiance to his class equal and fellow soldier above his allegiance to Waller and the greater power structure, breaks the strike, and they all make their way to the final battle.

There, Enchantress tries to tempt the Squad, showing Deadshot, Flagg, Harley, and El Diablo their most deeply held wishes. Deadshot wishes for personal glory—an alternate series of events where instead of being arrested by Batman, he got the upper hand and killed him. Flagg wishes for his June back without the dangerous Enchantress side. Harley wishes for a “normal”, middle-class existence with her Mr. J. Diablo just wants to right his wrongs—he wants to be at home with his wife and children, but he realizes he can’t have that. America can’t forgive itself for its sins—we can’t wipe Dresden, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, My Lai, and Agent Orange under the rug and pretend, to quote Hillary Clinton, that “America is great because America is good”. America is great, yes, but not in the sense of being good. America is one of the most powerful nations on Earth, but it’s not because we’ve been a shining city on a hill. We’ve gained strength through our sins, profiting off slavery, genocide, and other methods of exploitation. The Amanda Waller/Enchantress dichotomy, then, takes on a political dimension—do we want to Make America Great Again, or can we recognize that America Was Never Great and hope to create a version of America that could deserve to be called not just Great, but Good? Diablo chooses the latter.

Eventually, Enchantress is defeated through mutual solidarity. El Diablo sacrifices himself for the rest of the team, purging his sins in death. Captain Boomerang is presented with a choice between personal gain and class solidarity—he can grab the watch he stole from the battlefield earlier or he can grab Enchantress’ heart. He chooses the heart. And in perhaps the most unsubtle bit of symbolism, Deadshot destroys the Enchantress using Harley’s gun, the cylinder of which is designed so that when he takes the shot, the HATE inscription rolls over and is replaced with LOVE. But having triumphed over evil, what is their reward? Amanda Waller sends them right back to jail, albeit with slightly better accommodations after Deadshot, Harley, and Croc make their demands. Boomerang asks for more, but when he’s pushed to act on it, he flinches. The message is clear—without greater societal change, the lower class will keep getting exploited by one evil to fight a greater evil.

Suicide Squad isn’t a great movie, but it is an interesting one. And in a blockbuster system where Marvel has made a factory out of producing just-good-enough action-ish comedy-ish movie-products, it’s nice to see something that isn’t afraid to be abrasive, confrontational, and just plain weird.