Spoilers of Transformers: The Movie ahead.

The animated show Transformers functions as a protection from the outside world. Life is a scary thing, and being a kid on planet Earth is often incomprehensible, so a television show where even cars are out to protect the Earth, and every episode the day is saved and status quo is restored, is a tremendous comfort. It would be easy to dismiss its concept as stupid, but in a world as dark and violent and painful as ours, taking refuge in a place of color and imagination is perhaps the best possible thing a young person can do.

Let me tell you about a man named Friedrich Nietzsche who also understood this.

Some people think of him as a nihilist, but he actually predated—and predicted—modern nihilism. He opposed it vehemently, claiming that above all else one should champion the power of man to find meaning despite life’s apparent meaninglessness. You can think of children as dumb for liking cartoons—or yourself as dumb for still liking them—but I don’t think Nietzsche would have agreed; within youthful idealism is the key to the most important part of human nature. This is the central message of his book Beyond Good and Evil, in which he posits that Good and Evil are just perspectives and words, and that their battles are false. What man must truly contend with is the crippling knowledge of his unimportance in a vast and empty universe—the lack of any purpose for good or evil to exist at all. The secret weapon against this that Nietzsche espouses is Love—the human ability to form attachments to things and care for them despite their apparent worthlessness, and furthermore, love in its transcendent, society-wide form—better known as Hope, or Faith.

While the original Transformers series captured something special in the eyes of children, the show’s formulaic nature and lack of any real plot was certainly a problem—it was merely Good vs. Evil, with no Love.

But then came Transformers: The Movie—one of the most advanced films about philosophy there is.

With this film, we are introduced to the series’ first real villain—prior to this, you had Megatron, a pretty goofy dude, always beaten by those pesky Autobots and subverted by his second-in-command. He was cartoonish, to say the least. But in the opening of the movie, we have Unicron—a gigantic being from the depths of space who eats an entire population alive, planet and all.

What is Unicron? Nihilism, of course. It—not ‘he’, it—is a seemingly unstoppable and all-consuming form of darkness not encountered often in children’s television. Worse, eating entire planets just happens to be its survival mechanism—it is simply trying to live on, in its own way. It’s not some Dark God with an evil plan—it’s a life-form that just happens to be bigger than you. It doesn’t kill you because it’s evil, it kills you because it hungers—a faith-shaking concept to anyone who used to think Megatron was about as bad as bad could get.

Speaking of Megatron, when he encounters Unicron in the depths of space, he comes back changed, now calling himself Galvatron. He, effectively, becomes a nihilist—his characterization in the rest of the show is that of a crazy person, his traumatic meeting with harsh meaningless reality having overwhelmed his ability to make sense of anything. He is what someone would become if they decided that since there is no absolute authority in the Universe, they can do whatever they want.

On top of all this doom, Optimus Prime dies, in a deeply disturbing scene. But, something prevails: the Matrix of Leadership stored in his chest (representing Hope) is passed on to the rest of the Autobots. This is an intensely Christian concept.

I’m not a Christian, but to me, the Bible is inherently atheist in its central message, so I have no problem discussing it. To broad-stroke: Jesus is basically ‘Job II’. Job is a weak story which claims that if you stay true to your convictions, good things will eventually come to you in the end. The story of Jesus improves on this idea significantly—it says that if you stay true to what you believe, you will still die, but you can live on in the hearts and minds of those you meet and inspire. You do not perish, but instead, gain everlasting life—not as some obscene soul-creature living out the rest of eternity, but in the form of the mark you left in the world. For example—by you, the reader, reading this article and remembering it, a piece of me is now living on in you. (Thanks, by the way!)

The Matrix’s power of Hope is incredible. When used by Galvatron, it changes Unicron—the vast, undefeatable planet-creature suddenly unfolds and becomes a giant transformer. From the simple addition of Hope to the equation, even the unending darkness of infinity becomes tangible and vulnerable. And when the autobot Hot Rod finally realizes the power of Hope and learns to open the Matrix, he briefly hears Optimus’ voice—this isn’t his soul popping out of some robot-afterlife to say ‘hi’ for a second, this is the power of others living on in you. The film’s credits promise that Optimus Prime will return, but he already has—in the form of Rodimus Prime, the new leader of the Autobots.

Hope itself is what destroys Unicron—not some superweapon or vulgar special attack or whatever. And with that, the film is saying yes, perhaps the world is full of things that will never be solved, and perhaps there is nothing out there that will justify your existence. But if you believe in yourself and those around you even when it seems pointless, you can conquer anything. Just as Nietzsche claimed, Hope and Love are the most powerful things in the Universe because they rail against the realms of possibility and twist reality itself—transformer-like—into a new form.

You might be thinking—could Transformers really be making reference to Nietzsche with this movie? Well, for one thing, the idea doesn’t have to have come specifically from good old Friedrich—it is possible for a thought to be formed without having read a specific person’s ideas.

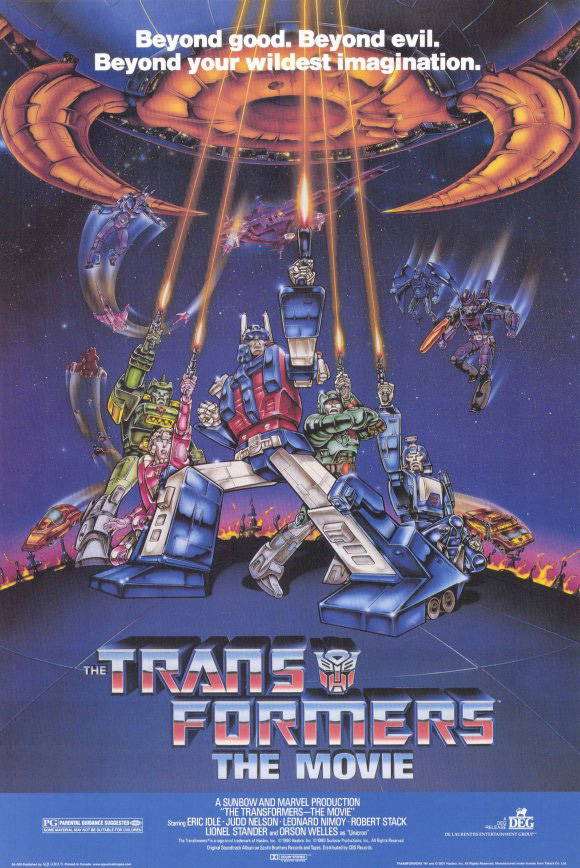

Secondly, and more importantly, take a look at the film’s tagline:

“Beyond Good. Beyond Evil. Beyond Your Wildest Imagination.”

Did the people who worked on this film understand the relevance of telling children to go beyond good and evil? I may never know for sure, but let’s just say I have Hope.

Nope.

Whuh?

I’m from the new video

lol same

same

I ran right over here excitedly! And it’s incredibly well-written, Harold! I’m especially fond of the Marshall Mcluhan/Star Wars essay.

This is pretty solid. Now if only we’d get the other half that was edited out of it, that’d be rad…

RELEASE THE HBOMBER CUT