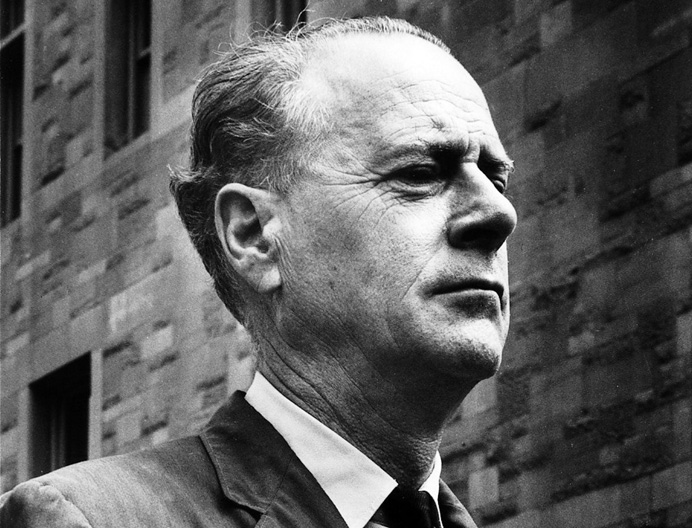

Marshall McLuhan. That’s right, that guy in the movie theater line scene in Annie Hall. McLuhan was a philosopher, and his contributions are right up there with those of Marx, Freud, and Nietzsche. His particular focus was on mediums, and how they influence our thinking. A person raised before the printing press is different, on a functional level, from a person raised with a television in their home in the 60s, or a person raised with Wikipedia constantly at their fingertips. Our very modes of thought are changed by the forms of information around us.

George Lucas has a huge interest in social science, and studied both sociology and anthropology in College when McLuhan was highly renowned. His first film, THX-1138, has McLuhan’s influence all over it— it’s set in a world where humans have been so shaped by inventions such as industry, economics, and security cameras that they have essentially become machines themselves, programmed to do whatever best serves the state or the economy. These humans even having computer-ish names—the title is eponymous. This is similar in spirit to Orwell’s 1984, in which an entirely new language is developed to try and repress people’s ability to rebel—if the very language you think in can’t even conceive of Big Brother as ‘bad’ (a word that doesn’t exist in Newspeak) how could you ever oppose the state? Language, besides being a tool for our expression, is the ultimate controller of our thoughts. You probably think in English, and because of that, your mind inherently lives in accordance with its rules, instead of your own. In that way, we are trapped by language.

In Star Wars, The Empire is presented as a similar institution to that of the society in THX, with banks of computers and security cameras everywhere. Their greatest weapon is literally a giant computer powered by thousands of bureaucrats, and the film is careful to associate the Death Star’s destruction of planet Alderaan with the flicking of switches in well-lit rooms by officers ‘just following orders’ at their daily grind. McLuhan’s concepts are present even in the iconic helmets of the Stormtroopers—the face is entirely covered, closing off any real human contact and dehumanizing them. What’s truly evil about The Empire is this system that figuratively and literally encloses them, which is why there are so many shots in A New Hope of security cameras exploding—this film is about fighting the Empire in a meaningful way, i.e., through the removal of the network that leads to people doing its bidding, rather than the killing any particular individual.

McLuhan predicted that mankind would reach a new level of freedom and advancement once it invented a technology that united people into a single consciousness where all voices can be heard. In this context, it becomes strikingly clear that The Force is a symbolic version of this idea. It is all-encompassing, and thus, leads us to commit ourselves to one another and make things better for everyone. It is a place from which the capacity for true egalitarian justice springs forth.

The Force is similar conceptually to what the Matrix of Leadership represents in Transformers: The Movie—radical, universe-altering existentialism. (The Autobots’ rallying cry of “Til all are one!” is even a pretty direct reference to the ideas of total unity represented in McLuhan’s prediction.) Both films are basically preaching universal justice through the opposition of the different ways we can be misled into fighting each other. And both A New Hope and Transformers: The Movie even feature a scene where the protagonist hears their dead mentor’s voice in their head—though gone, the old lives on through the new. You don’t need ghosts to be literally real for this to be true—Obi-Wan lives on, more powerful than Darth Vader can possibly imagine, as an idea. Many folks claim that Vader is a Christ-figure for being ‘reborn’ in Return of the Jedi, but Kenobi did it in the very first film.

A New Hope has a lot of McLuhanist jokes about different mediums and their limitations—Luke gets snuck up on by a Tusken Raider because he’s busy using binoculars; Tusken Raiders travel single-file, so you can’t tell how many there are from their footsteps; Han Solo almost gets away with imitating a Stormtrooper over the radio because the cameras are down; C3PO can’t distinguish between shouts of pain and elation because he’s using a radio and can’t see what’s going on visually. The film even makes fun of the limitations of the viewer’s perception—R2D2 and Chewbacca both speak in unintelligible noises, but the characters around them can understand them. And in the end of Return of the Jedi, C3PO is made king of a race of animals that no one else can understand, and helps everyone learn to communicate with one another. Through this, the film is telling the audience that maybe, one day, we will finally all understand each other. That is the true spirit of Star Wars.