As I Lay Dying (2013)

Directed by James Franco

Screenplay by James Franco and Matt Rager

Based on the novel by William Faulkner

Spoiler-free.

As I Lay Dying is James Franco’s seventh feature-length film as a director, but only his second to receive much of a release. The first was The Broken Tower, a biography of the poet Hart Crane, which was completed as his MFA thesis for NYU. Despite the fact that Focus picked it up and it starred Franco and Michael Shannon, that film felt like a student film through and through, and Franco received the critical berating he earned. Two years later, he’s back with another difficult work of American Modernism.

James Franco kind of stepped into a minefield with this one. The literary crowd is unimpressed with his famoused-my-way-into-a-book-deal poetry and prose, and his more mainstream fans are turned off by his occasional excursions into ‘pretentious shit’. Here, then, is a way to alienate two distinct fan bases at once.

I must just be a contrarian, because these are the sorts of films that interest me most.

Faulkner’s short novel As I Lay Dying has a reputation for “unfilmability” which, more than anything, points to a very specific and, I think, limited concept of adaptation. The form of As I Lay Dying is unreproducible in another medium—it’s a web of oblique introspection which is inherently and deeply literary. But the content of As I Lay Dying—a poor family traveling across a belabored country to inter their dead mother—is practically begging to be a film.

William Faulkner has a dicey record, cinematically. He was a writer for Howard Hawks, contributing to The Big Sleep and To Have and Have Not, among others. But according to Leigh Brackett, very little of Faulkner’s dialogue made it to screen because it was, well, Faulknerian as all hell. For those who don’t know what that means, his novel Absalom, Absalom! contains the longest sentence in the English language.

Like most great authors, the best film versions of Faulkner’s books bear little resemblance, beyond mood, to the text—Intruder in the Dust, The Tarnished Angels, The Story of Temple Drake, and The Long Hot Summer all bear the impressions of another strong, cinematic personality through which Faulkner’s complicated, elliptical text is strained. A quick tipoff of this fact is that three of those four films have different titles from their literary sources.

A successful A I Lay Dying film, then, should ideally walk a tightrope, retaining its evocative and striking premise and setting while standing on its own two feet as the personal and complete creation of a filmmaker, not an author.

So how’d Franco do? Well, it’s probably as good a screenplay adaptation as you can get. Franco and his partner Matthew Rager (who’s also onboard for the screenplay for Franco’s upcoming The Sound and the Fury, another Faulker adaptation) crack a fast pace, without getting bogged down in the referential tedium that could sink a project like this. Franco has mentioned in interviews that a good part of Rager’s job was paring down Franco’s 160 page first draft (almost as long as the novel itself) and he did a magnificent job. There’s a strong sense of time and place, particularly the gulf between the modestly poor and the truly poor of the hardscrabble south.

But a film ain’t a screenplay, and that’s where things get a bit more controversial. As a director, Franco seems eager to explore and experiment with form. This film has the feel of the New Hollywood stuff of the 1960s and 1970s—or maybe, more accurately, the current revival of that style. In a weird way, if you liked The Devil’s Rejects, you might like this one. The form itself is odd and aggressive—much of it is monologues delivered Spike Lee style to the camera. These are tricky, and occasionally they work very well, but other times, they seem to just clutter up the screen.

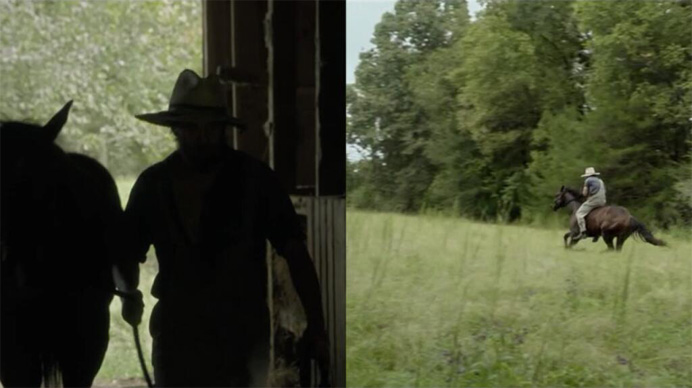

The most striking element is the near-constant use of split screen which, like the film itself, is an ambitious and mostly good idea which doesn’t quite reach its full potential. Faulkner has a very particular emphasis on time as mutable and subjective in quality. One person’s perception of time is not another’s. Darl yearns to “ravel out into time”—an experience the split screens provide. At its best, the split screen shows the same shot played a few frames off, or the same moment from opposite points of view. They loop time, stutter it, throw it into disarray. But see, to compose for split screen, you need to emphasize vertical compositions—you’re essentially composing for an iPhone ratio. Franco falls down on that. There are some great shots in this film, but they’re often lost in cropping, and too much of the time, the screen is merely cluttered.

The split screen feels like an editing decision rather than a holistic filmmaking decision. It’s a shame, because within it all, there are some truly great performances. Tim Blake Nelson steals the show with a snakelike untrustworthiness that seeps from every inch of Anse; Logan Marshall-Green puts in good work as the underused Jewel (good example of the decisions in adaptation there—my version would’ve had more Jewel than Darl); Franco himself is solid but unremarkable—he’s probably stretched too thin to have taken the lead; and the real gem is Danny McBride, channeling the frustrated undercurrents of Kenny Powers into a disrespected schlub of a neighbor. A carefully composed hand in those split screens and monologues would’ve brought these performances to a fine finish, but overall, they tend to feel secondary to formalist tricks.

Despite its foibles, we’re left with a pretty promising feat for a professional debut. James Franco took something nobody thought could be done and did it, succeeding more than he fails. He’s grown a lot as a filmmaker, but has a great deal more growing to do. I’m exciting to see if and how he does.

3 1/2 out of 5.

Skype has opened up its website-structured client beta to the

entire world, following establishing it broadly in the

U.S. and U.K. before this month. Skype for Internet also now supports Linux and Chromebook for immediate online

messaging conversation (no voice and video but, individuals call for a plug-in set up).

The increase in the beta brings assistance for an extended

listing of different languages to assist bolster that

worldwide usability