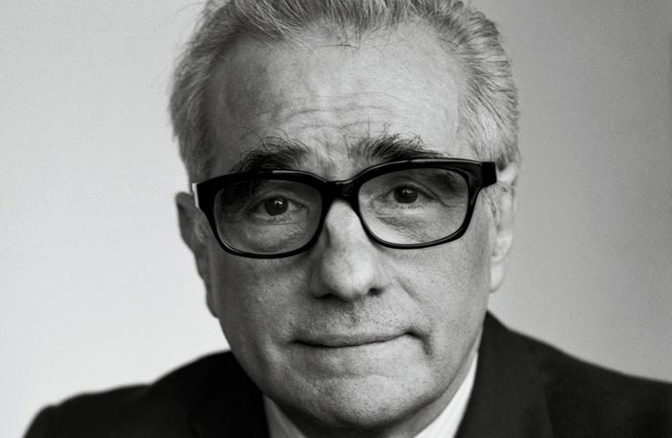

As you can probably tell by my posts here so far, I don’t like many movies. Movies suck. But even an old curmudgeon like me can’t help but love Martin Scorsese.

What can be said about Scorsese that hasn’t already been said? Well, I bet nobody has said to him, ‘Hey dude what the fuck were you thinking when you made Kundun? Stick to New York, asshole.’ Kundun is so bad people don’t even talk about it. Which really shows just how beloved the guy is. When he makes an epic embarrassment, people just brush it under the rug (yet for some reason, nobody extends his bud De Palma that courtesy).

Forgetting Kundun, when Scorsese makes a bad movie you get Raging Bull. A film that, with age, is rivaling Citizen Kane as the popular choice for best movie ever made. I like to pick on Raging Bull for that reason, because at its heart, Raging Bull is a vapid, boring, meandering, overlong mess about nothing. However, the thing is, if you’re a movie geek, there’s a ton to love about Raging Bull, and I certainly do love it. Whereas almost all other ‘art films’ are exercises in masturbatory, inaccessible nothingness, Raging Bull is a cinephile’s delight. It’s a visceral film class, expertly constructed by a team of artists that really do know how to make movies. Raging Bull may not have a point, but those brilliantly-realized fight scenes sure make you think it does. (Really it’s just about a guy being angry, and we have no idea why, and it’s never really explored.)

So what happens when Marty makes a good movie? When Martin Scorsese makes a good movie you get Goodfellas, one of the most fun, interesting, intoxicating, emotional, and amazing movies of all time. Frank Darabont said that when he was making The Shawshank Redemption, he watched Goodfellas every Sunday. You can tell.

The genius of Goodfellas is what it doesn’t show. The Lufthansa heist is hyped up—but then happens off screen. The scene in the shower where Henry hears about the heist on the news is much more powerful than any dramatization could be. The whole movie is really just a guy (and a girl) telling a story. And it’s not even a great story. It’s kind of just an interesting story. But the detailed web of behaviors, accents, dialogue, colors, clothing, performances, and, of course, moving compositions, hold it all together. One of my favorite things about the movie, visually, is that there are very few closeups or wide shots. It’s a world of mediums where we see someones face, the faces around them, and nothing outside that. The world around them is in the distance—if we see it, the medium lens puts it far away, out of focus.

What makes Scorsese genuinely better than 99% of other ‘art’ filmmakers is that his style is truly expressive. The obvious example being the Copacabana shot. This shot is complicated as fuck, but with purpose. That’s a good director. Boogie Nights, Rope, Irreversible, and Russian Ark all have very long, complicated takes in them too—but why? To what end? None of those shots express anything. The opening of Boogie Nights does it simply because Scorsese did it—and the other three are just gimmicky. In fact, the only other truly expressive long take I can think of is the opening of Touch of Evil because it used the device of a ticking clock.

Ultimately, Goodfellas is everything you could ever ask for in a movie—no bad scenes, endlessly quotable, a frenetic visual feast, and nuanced to the point that the minutia is often more entertaining than the main elements. I mean it’s got ”half a fag”, ”what are you some kind of sick maniac”, and the entire helicopter sequence. Those are worth the price of admission alone.

Martin Scorsese is a gateway drug. His work in general is quite visceral and tranquil—like marijuana. His movies wrap around you and make you think you’re reaching a higher consciousness, when really, you’re just watching a fucking movie. (And I don’t say that to belittle his work. Just stating the facts. Also, I’m not a spaced out hippie—I’ve literally only smoked weed one time and never done any other drug. I’m just making a metaphor.)

The casual Scorsese user can delight in the occasional trip into Scorsese world, and remain safe within the confines of a truly fun and transcendent movie going experience (as long as he or she avoids Kundun and Boxcar Bertha). However, for the burgeoning cinephile, what lies beyond his work is a dark pit of god-awful ‘art films’ and ‘classics’ laced with boring scenes and incomprehensible stylistic choices. I’m talking of course about Scorsese’s contemporaries and influencers—guys like Altman, Malick and Cassavetes. Watching them is like doing heroin—it seems fun, but then you’ve done it and your life is basically over.

I’m currently reading Roger Ebert’s book on Scorsese, and I’m remembering my own ‘Personal Journey Through American Movies’ as a curious and hungry hyper-intellectual thirteen year old with a chip on his shoulder. My story is simple—I saw Jurassic Park when I was six and immediately became a Spielberg-head and would obsessively watch Indiana Jones, Close Encounters, Jaws, and Poltergeist (yes, directed by Tobe Hooper, but ya know). My parents and grandparents were also cinephiles and introduced me to many wonderful movies like Tremors, The Incredible Shrinking Man, Back to the Future, Ghostbusters, etc. I am forever indebted to my Grandpa for showing me Plan 9 From Outer Space at age eight and opening my mind up to irony—which I guess made me a ‘hipster’ all the way back then. I got irony before it was ‘cool’.

However, a detour in my “tweens” led me to thinking I would be a goalie in the NHL, and my filmmaking limb was severed—but not cauterized. By age thirteen, I was a put-upon nerdy kid who tried to fit in by being smarter than everybody else. And when you decide to begin a descent into cinephiledom, Scorsese is the most obvious place to start. His movies are just popular enough to be household names, but just ‘art’ enough for you to be considered smart for watching them. They’re both iconic and subversive, a part of the counter culture that basically just became culture—like the Ramones.

But here’s the thing—it’s difficult for a thirteen year old to watch Taxi Driver, because it’s, for lack of a better word, boring. But what happens at that age is you want to believe. You want to be connected to that world that understands a movie like Taxi Driver, so you appreciate dolly shots that pan away from characters to empty hallways, or long zooms into Alka-Seltzer. Ironically, these things are to be appreciated as a result of the fact that at their core they are simplistic visual symbols to be taken at face value, and nothing more. Their effectiveness lies in their blatancy. In fact, there’s nothing not to understand about Taxi Driver (except maybe the inexplicable ending when a psycho killer is turned into a hero.) But overall it’s just kind of… boring. Yet the truth is, Taxi Driver is a great thing. It’s a great thing because there’s a ton of really great moments, and it not culminating into a fully-realized thing isn’t such a big deal because there’s just so much for a cinephile to delight in.

Roger Ebert loves Scorsese though. It’s like, nuts. Since his book is just a collection of reviews, it’s funny because you have to keep reading over and over the phrase “the best American filmmaker” because he uses it in every goddamn review of a Scorsese thing. When he’s reviewing a great movie of his, he reminds us of it flat out, and when he’s reviewing a bad movie of his, he praises it by basically saying ‘from a lesser filmmaker, this would be a work of genius, but from the greatest American filmmaker, it’s just kind of eh.’

I was pleasantly surprised to find out that Ebert loves After Hours as much as I do. (Great minds!) It’s unequivocally Scorsese’s second best movie—and probably his most under-seen. And it’s said that Scorsese himself doesn’t particularly like this one that much. Not to be weird, but I think that’s partially why it’s good. Scorsese is usually so theme-obsessed that he forgets about story. This happens with many ‘art’ directors—they get too caught up in their themes that they forget that less is more, and that story is everything. Kundun is obviously the pit here, but movies like Raging Bull, Taxi Driver and Mean Streets are all examples, too. They end up being about nothing by wanting to be about too much. After Hours isn’t like that. It’s not typical Scorsese (it isn’t about Catholic guilt, for once) and I suspect that is both why it’s good and why he doesn’t like it as much. It’s simply about a dude trying to get home and weird shit keeps happening to him. It’s a tight, succinct, fun story. (An 80’s movie, basically.) It’s refreshing to know that Marty can work outside all of his comfort-zones—De Niro, Italians, old Hollywood nonsense—and still make a great thing. The only example I can think of, of other ‘art’ filmmakers doing this, is David Lynch’s The Straight Story (one of his better efforts).

I’m always impressed that filmmakers of that generation were and are able to make good movies at all, when what they grew up on is so bad. How The Searchers becomes Star Wars is beyond me. This is most striking when you watch A Personal Journey with Martin Scorsese through American Movies, a very long documentary hosted by Scorsese, in which he ushers you through the movies that influenced him as a kid. It is impossible for me to put myself in the late 40’s as a pre teen. I can’t even fathom it. But if Super 8 is proof of anything, it’s that growing up on good movies doesn’t necessarily mean one will make good movies. So maybe there is something to be said for being raised on bad ones. They certainly inspire ingenuity.

A camera doesn’t have to move. The basic building blocks of cinematic grammar don’t require it. Moving the camera, for purposes outside of following an action, is automatically a form of expression. But whereas other stylists use jagged jump cuts and a hand-held camera to falsely heighten bland scenes, Scorsese uses his camera to bring out the emotion underneath. It is true that his contemporaries (Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Brian De Palma) all did the same, and all made better movies. But none made them with the same delightful zest that made you excited about movies themselves.

Mean Streets is not a good movie, but its use of contemporary pop songs is in fact more innovative than Lucas’s American Graffiti (also an utterly forgettable movie). Whereas Lucas uses his songs as a score, a musical bed to inform emotion and evoke nostalgia, Scorsese finds the emotional pulse of the music and blends it with his visuals to create a wholly other emotion, a tone created by the totality of all the elements. For whatever reason, Scorsese’s mind intuits movement, cutting, and music in a way nobody has before or since, and the results are staggering.

There is literally no better example of this in the history of cinema than the Layla montage in Goodfellas, perhaps one of the most emotional sequences in all of cinema. He even played the track live on set to get the right timing and rhythm of the truck doors opening for the long crane shot that reveals Corbone in the freezer. On the DVD featurette, you can see footage of Marty feverishly editing that very scene with Thelma Schoonmacher (hard to tell where her genius begins and Scorsese’s ends). His intensity in that moment is that of a Van Gogh-esque painter (incidentally, whom he once portrayed in Kurosawa’s Dreams) as he discusses the perfect cutting formula for the scene.

But really, the best and possibly most surprising thing about Scorsese’s work is that his ingenuity reeks of inevitability. What I mean is, for example, there are some melodies that are so simple and infectious that they were bound to be written. They feel perfectly inevitable. For instance, say, The Rolling Stones’ “Satisfaction”. The shot in Taxi Driver when Travis is on the phone being rejected by Betsy, and the camera dollies away from him to the empty hallway, is like this too. The symbolism is so obvious that it doesn’t even seem like an idea. You accept it readily because your brain makes sense of its intention immediately—and it takes a second to realize that you’ve never seen anything like that in any movie before. That is invisible, expressive, truly advanced filmmaking at its best.

When Ebert was sick and he had guest hosts on his show, Kevin Smith took over for a week or so. He reviewed The Departed and loved it. He said there should be a genre for Scorsese himself. He’s right.