Shane (1953)

Directed by George Stevens

Screenplay by A.B. Guthrie Jr.

Additional Dialogue by Jack Sher

Based on the novel by Jack Schaefer

My great fear—and sadly this is true—is the possibility, however remote, that I’ll get sucked through time into a distant and shattered future where I’ll be forced to rebuild human civilization. Digging through our fallen society’s vast underground archives, I alone would have to bridge eons of cultural distance and reintroduce art to a numbed world.

Where do you begin? How do you introduce someone to rock and roll? What captures the essence of the form? What is the most rock and roll album? Sticky Fingers? Born To Run? Rubber Soul? I could never decide. What is the most modernist novel? What is the most Shakespearian of Shakespeare’s plays? What is the most sitcom sitcom? It’s a series of Sophie’s choices, each more stressful than the last.

But in this complicated world, one thing is clear:

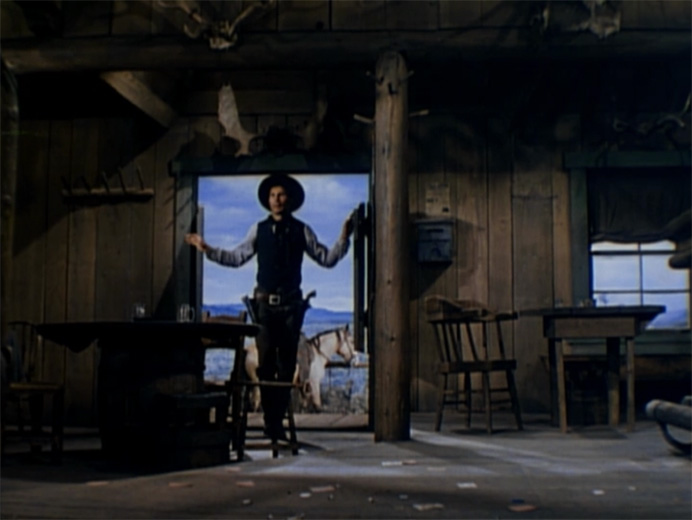

Shane is the most western western.

If there’s one movie that can encapsulate the entire genre—what it looked like, sounded like, felt like, worried about—it’s Shane.

Shane is the story of a gunslinger with a heart of gold, a mysterious and unpredictable man who rides into a range war and sets things right. It’s a story about sacrifice and lust, and a story about growing up, about a child’s tendency to see godhood in adulthood, about love and shame and shame in love, about growing old and seeing your lifestyle become irrelevant and untenable. It’s subtle and openhearted with rich characters and a vivid world, the kind of film that children love for its simplicity and adults love for its complexity, and that morose hormonal teenagers, uncomfortable with emotions and patience, hate.

The whole movie is in its opening scene, a 9 minute short film in and of itself, set entirely outside, on location in the impossible vastness and rain-soaked richness of Wyoming.

Young Joey Starrett watches Shane ride across his family’s homestead. Shane, polite but clearly dangerous, asks permission of Joey’s father to cut through his land. Permission is granted, but it’s shaky. Joey cocks his play rifle, Shane wheels with gun drawn at the sound. Then, a misunderstanding—Joey’s father thinks Shane is “a Ryker.” Shane doesn’t know what that means. Threats, etc. Shane leaves just as the Rykers show up—it’s a cattle baron and his posse. They want the Starrett land and they’re ready to take it by force. The Starretts hold their ground but they’re outnumbered and have no leverage.

Suddenly Ryker demurs. “Who are you?”

Shane, our Shane, answers: “I’m a friend of Starrett’s.” He’s standing beside the Starrett family, his gun gleaming in the sun.

The balance of power has shifted.

Shane was released in 1953, the same year as Anthony Mann’s masterpiece The Naked Spur, the middle part of the five film exploration of the cowboy he made with Jimmy Stewart. It was three years after John Ford concluded his seminal Cavalry Trilogy with Rio Grande and three years before Ford exploded the genre with The Searchers. The western genre of 1953 was surefooted and mature, in the midst of an explosion of talent and confidence, and unlike the by-and-large clear-conscienced westerns of the 1930s and ’40s*, in which death is fast and bloodless, or the hardboiled westerns of the 1960s and ’70s in which death is exciting and satisfying, the westerns of the 1950s were horrified to the core by death. The greats of the era—films like The Searchers, Man from Del Rio, High Noon, and The Gunfighter—are usually low-body count films in which each spent bullet is a frightening and potentially life-altering event (there’s a great moment in Jacques Tourneur’s 1955 film Wichita when Wyatt Earp casually warns a traveller to stay away from the windows at night because of stray bullets). These are siege films—films about how death is constantly at the door but life must be lived anyway.

I don’t think any film captures this hatred of death and love of life more than Shane. Director George Stevens, who helped liberate Dachau and filmed a lot of the most horrifying concentration camp footage, confronts death head-on. “A gun is a tool,” Shane tells us, “no better or worse than any other,” but the guns of Shane changed the way we filmed guns. Far from the “pings!” and “pops!” of most movie guns, the gunfire sound effects in this film are sourced from a cannon fired in a trash can, and the victims of gun violence are yanked across the set on wires—a first in American film, now industry standard. Guns are transgressive, loud and destructive, definitive and world-altering.

Shane is pure iconography. The man in the white hat tall against the sun, the bad man in the black hat sneering and whispering threats. It has that quality Casablanca and Forbidden Planet have, where it has permeated the culture and become so much a part of so many later films, and yet so distinctive, pure and singular, that it feels like magic. This works doubly to the film’s advantage, since it’s all from the perspective of a child. Little Joey Starrett, played by 11-year-old Brandon De Wilde, gets a bit of flak nowadays, but I think his strange, lonely, idealistic kid is one of the great child performances in film history.

Joey idolizes Shane from the moment he sees him. He recognizes strength in the man and Shane, anxious for domesticity, reciprocates. Watch their first interaction. Joey worries Shane is going to criticize him for staring, but Shane praises him and assures him “he’ll make his mark some day.” Their interactions are defined by guns. Joey cocks his rifle and is awestruck by Shane’s fast draw. Later, Shane teaches him how to fire a gun, in a vaguely unsettling and boundary-crossing scene. A decade later, Brandon De Wilde reprised this role in Hud, where he also played an idealistic kid dogging a dangerous westerner.

Shane’s relationship with the rest of the Starrett family is just as captivating —he and the father Joe have a mutual respect tinged with mutual understated jealousy, and Shane and Joe’s wife/Joey’s mother Marion Starrett share an amazing romance, a romance which is never addressed in dialogue, not once in the entire film. It’s all implied, and the engine of their mutual interest drives the story. The idea of a wordless romance was borrowed for The Searchers. It’s a perfect fit for the western, a genre packed with subtext about honor and masculinity, a genre in which speech is often a sign of weakness.

That said, there’s a pretty sizable amount of talking in Shane, the homey warm conversing of a small town. We get the sense that this community existed long before Shane and would exist without his ever having appeared. In a move unusual for a western, a lot of the actions and dialogue, especially in the first half, occur without Shane. He is a quiet, mannered presence, coiled and distant. He speaks softly and sweetly, even thanking Marion for her “elegant” dinner (when was the last time you heard a western hero call something “elegant”?), but unlike the relaxed presence of the real homesteaders, domesticity is an uneasy fit. But we like Shane, and we want him to be okay, even though we know the two-men-one-woman arrangement is untenable. Like I said, a mature film that’s at once complex and simple.

Watch Shane for its story, then watch it again to explore the world it has created, to learn its rhythms and watch the way background townsfolk interact with one another and with Shane. One of my favorite moments in the film comes when Shane advises the homesteaders of what the Ryker’s hired gunslinger will do. A background character, who we’ve seen in a few scenes around town but never paid much attention to, looks at Shane with the complicated look a family man gives a tentatively-friendly gunfighter and says “you sure do know a lot about this business.” Earlier, Shane goes to the general store to buy Joey a soda. “Do you have any soda pop?” he asks the store owner, and that man, tired of violence and certain it’s there to stay, sighs an answer, “sure did, I only wish more men drank it.” It’s an amazingly complex and layered world, perhaps not equalled until McCabe and Mrs. Miller, and even then, only barely. There’s nothing else quite like Shane.

Watch Shane.

In the end, this is my ultimate tribute to Shane: I tried to write this review while watching the film, a film I know as well as any, a film I’ve seen time and time again my whole life, but I couldn’t keep my eyes off the screen long enough to get any sentences down.

*Two major exceptions: Ford’s 1946 My Darling Clementine and Wellman’s 1943 The Ox-Bow Incident, two unequivocal masterpieces about the horror of violence.

Great words here. I know what you mean about writing as you watch this grand film. It would probably take you six months.

I think that Shane is, if not the best film of all time, the best Western of all time.

Great performances here, Ladd, Heflin, Arthur, De Wilde, Palance, Elisha Cook Jr (?), Ben Johnson (brief, but powerful), the Rykers………..but there is way more than the performances here. It’s the sound……..the gunfire (like cannons), music…….so serene at times…….then like war drums pounding, the scenery, the mountains, the clouds, the shade, the mud, the town, Palance’s boots……..I could go on!

A marvelous cinematic achievement!

I would like to know more about the Colt 45 that Ben Johnson is wearing; any information would be very helpful.

Thanks!

Sammy Rubin