Robocop (2014)

Directed by José Padilha

Screenplay by Joshua Zetumer

117 min.

Very minor spoilers ahead.

When they rolled that screen open to 2.35:1, I knew it wasn’t going to be like Verhoeven’s. The original Robocop is a minor masterpiece, one of the most cutting satires of the 20th century. It’s dingy, clunky, sarcastic, and howling—just like the ‘80s that spawned it. Our new Robocop—which is, for all practical purposes, the second Robocop remake in recent memory, counting the spectacular Dredd—is none of those things. It’s shiny, sleek, and “tactical,” as Michael Keaton’s character says.

The memorable ultra-violence of the original is gone. In its place, there’s a smooth, sanitized finish over everything, which gives it all a sort of uncanny creepiness—a quality best exploited in one of the film’s high points, in which we learn just where Alex Murphy ends and Robocop begins.

Structurally, it isn’t as tight as the original. Though Michael Keaton is spectacular as Evil Steve Jobs, and OmniCorp on the whole is brimming with really fun villains, nothing really comes to a head and none of them ever quite get to do anything suitably exciting. Still, when it works, it works. There’s a very interesting and well done plot about the trials of Robocop’s family who, unlike in the original, know exactly what happened to him. We get some surprisingly heart-wrenching moments, like when Robocop keeps zooming in a video chat screen so that his family can’t see his robot body, and some really sharp politics, like when Robocop almost literally escapes from an iPod factory in rural China.

That sounds funny, and I guess it kind of is, but on the whole this film isn’t. It’s getting some flack about that, but I appreciate the fact that it found its own path. The best parts of it are the parts farthest removed from the original, and the worst parts are a few shoehorned references to Verhoeven’s. But it ain’t funny—certainly never like the hysterical original. I have a theory about that, and my theory is, times change.

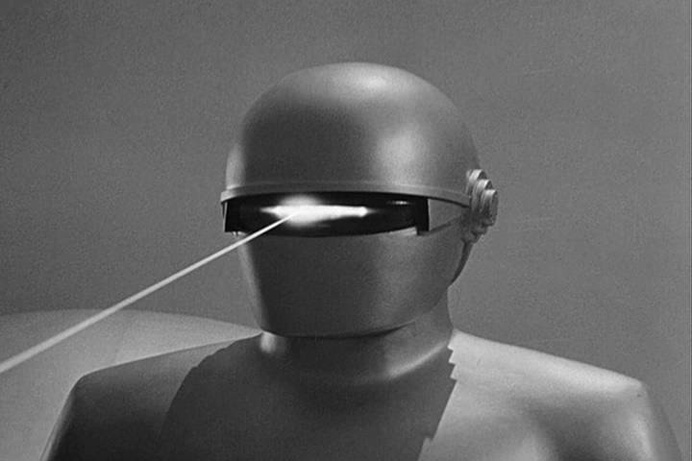

In this movie, Robocop has a pretty sweet panning red eye. This is a feature Robocop had in his horrible Saturday morning cartoon. Seeing it now throws my mind right to Battlestar Galactica, a major text in “what’s a human and what’s a robot?” cinema, but in the end it’s an image that, ultimately, divides back to Gort’s eye laser in the seminal The Day the Earth Stood Still.

In 1951—the year that defined the rubric of science fiction as we now know it—Robert Wise’s incisive film climaxed with the concept of indestructible, insensate, indefatigable robot policemen patrolling the streets. The Day the Earth Stood Still was conceived at the very dawn of an era in which the pressing of a single button could end all life on earth. This was one year after Joseph McCarthy announced the existence of 205 Communists in the State Department, two years after the Soviets got the bomb, and six years after the end of the costliest war in human history—a war set off by a handful of unchecked autocrats. The great question on the lips of the world was “Who should be in charge?” Decentralized power had let Stalins and Hitlers sprout unchallenged. Smaller nations had nobody to stand up for them against the onslaught of determined psychopaths. Meanwhile, Franklin Roosevelt steered America through the troubled waters of depression and war, leaving us the strongest and most self-assured we had yet been. For that historical moment, it took an FDR to beat a Hitler—power was a delicate commodity, to be trusted only in the most expert, scientific, ambitious hands. In 1951, the concept of the all-knowing Klaatu and the all-powerful Gort was something of a comfort. An incorruptible, inhuman arbiter may be somewhat intimidating, but was, ultimately, for the moment, a utopian vision.

But times change. Eisenhower warned of a “military-industrial complex,” and then Kennedy got killed, ushering in an era of ineffective and/or corrupt presidents. A massive social revolution came and went, killed by cocaine, Nixon, and weariness. American cars got terrible; the Soviets discovered blue jeans. America, insecure and nostalgic, was so desperate for John Wayne they were willing to settle for the guy from Cattle Queen of Montana instead. The stage was set for the ascendance of Ronald Reagan, our first vampire president. And so, for a whole decade, one of the worst actors of his generation laid siege to Latin America, tore apart black families with vindictive crack sentencing, made moves to weaponize space, and put Scalia in the Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, science fiction got very pessimistic in the ‘60s, very optimistic in the late ‘70s, then back to pessimistic and plain old jaded right quick in the ‘80s. After Johnson, who threw American bodies into Vietnamese bullets like he was playing that carnival game with the milk bottles, after Nixon, who was basically a more tedious Iago, and after Reagan—fucking Reagan—the concept of an enforcer with absolute power got less rosy. Robots mutated from benevolent protectors like Gort and Robby to unstoppable monsters like The Terminator and the killbots from Chopping Mall.

This is sort of an interesting thing to me, because if you really look at The Day the Earth Stood Still and Paul Verhoeven’s original Robocop, the exact utopian element of 1951 became the dystopian core of 1987. What is the ED-209, but a version of Gort? Hell, Robocop himself even has practically the same head.

Robocop ’87 puts the whole Reaganist optimism on blast by presenting the logical conclusion of the era’s doctrine and figurehead—a much beloved madman with a quick draw and a basic inability to see human life as anything beyond assets. It’s a crazy, bitter, hilarious glimpse at the kind of world The Terminator would call “one possible future, from your point of view”.

Robocop is a bitter thought experiment, a vision of the logical end point of craven capitalism. The film imagines the grotesqueness of a privatized military, a privatized space program, and a world of robber barons with absolutely no accountability. A world where the best of us is a corporate-owned Frankenstein who talks like a space cowboy. And, silliest of all, a world where all of this craziness is packaged in the populace’s daily entertainment/news cocktail (“Go Robo!”).

What a funny, crazy, mixed-up world Robocop imagines. What a fun joke that was in 1987.

But times change.

What was a grim, theoretical joke in 1987 is just a part of life in 2014. A privatized military? The ghouls at Blackwater (now Academi, formerly the even more Bond villainy “Xe”) now have a goddamn video game. Privatized space program? Branson’s about all we have left after decades of merciless NASA budget cuts. How can you joke about Lee Iacocca Elementary School when we came within spitting distance of President Mitt Romney?

Hell, even the character of Robocop himself has been swallowed up in commercialism. Since saving Detroit from Dick Jones, Robocop has gone on to hawking fried chicken, wrestling, and starring in his very own children’s cartoon. The revolution was televised—and that’s what defeated it.

So what’s to joke about anymore? Robocop is no longer comedy. It’s barely even science fiction.

Great article!

I would like to point out that RoboCop actually had two live-action series and two cartoons/animated series ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RoboCop_(franchise)#Television_series ), and the one cited above is actually the better, less market-washed of the two animated series. When they moved RoboCop from a strong feature satire film into a market product (i.e. everything after the first RoboCop film), I think that’s when it stopped being effectively relevant.