The Girl Next Door absolutely wrecked me. I can think of no other horror movie that has been able to bring me to tears. That’s such a rare emotion for the genre. But, when you think about it, tragedy really is the scariest thing—the people you love, in horrible situations, suffering, the threat of their death looming. Horror movies, to truly be horrific, should be tragedies, at least somewhat. Unfortunately, more often than not, they’re merely gory action movies or tongue-in-cheek comedies. If that’s not clear to you now, it certainly will be after watching this film.

Recently, I had the chance to sit down and pick the brain of its director, Gregory Wilson:

The Girl Next Door is one of my absolute favorite horror movies, but it’s hard for me to even call it a horror movie, because the way that it resonates for me most is as a tragic romance. It gets me in the heart, whereas most horror movies, even though they tend to center around boyfriends and girlfriends and families, you rarely really feel the love, or when deaths occur, the loss. It’s almost a total afterthought, whereas with this movie, the entire foundation is built on love, and the fear of loss. How would you classify this movie? And, did you run into any difficulties as far as classifying it, and its promotion and marketing?

Well first of all, thank you for the question. It’s a great question. When I was pitching for the film, I knew that the producers were already speaking to several directors. What I discovered later on was the consistent theme with the other directors was that they were focusing on the horror elements. I always looked at The Girl Next Door as a social horror, as opposed to your traditional fantasy horrors—your Freddy Kreugers and your Friday the 13ths, etcetera. So my pitch to them was that the social horror element is a crucial element. I saw a coming of age story among all the kids that were involved, all of them, and I also saw an unfulfilled love story between the two main characters. And that was the approach. I said there are really three different stories here, and then of course you have the child abuse element, which to me was the social horror element. And that’s why, even though it’s classified as a horror film, it’s very much a dark drama.

With regard to the second part of your question, the classification, originally the MPAA wanted to classify The Girl Next Door as NC-17, and I remember that myself, and the two producers, got on the phone with the ratings board. The producers asked me to pretty much talk to them and see if I could, not necessarily convince them, but explain to them my approach and why I believe that the film deserves no more than an R rating. Basically, what I told them was that the way that I shot the film, I was very respectful and very sensitive to the material. I tried to leave a little bit more to the imagination. I always believe, as a director, the audience can bring more to a film than a filmmaker can, because the audience is completely free, as opposed to, when a Director presents the story to them, we’re locked into whatever our vision is. This is why I made those certain directorial decisions, in regards to how I was shooting the scenes. The board eventually agreed, and gave us the R rating that we were looking for.

That must’ve been quite the process—I’ve heard so many horror stories about filmmakers dealing with the MPAA, fighting from NC-17 to R.

Yes, it’s always a fight. It’s always a fight.

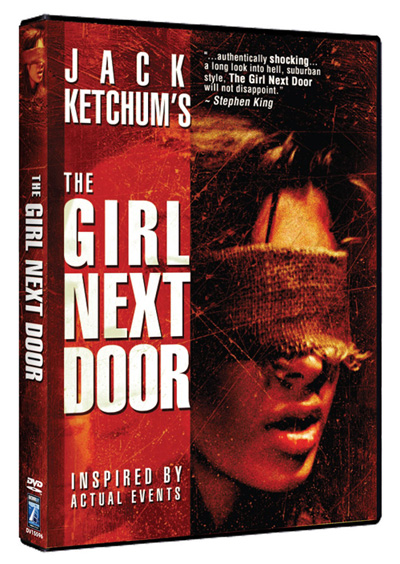

How do you feel about the DVD cover of the film? It seems to represent a much more exploitation-y movie, and it’s very different from the posters. Do you feel that any of the posters or promotional material really nailed the vibe of the film?

It’s funny, I get a lot of questions about the DVD cover and the various one-sheets that have come out, and my answer is the same—I think a lot of people already have a preconceived notion, either based on the book or based on what they already know about the film, so a lot of times, again, it falls on the audience, and people projecting.

I personally and professionally had no problem with the image of the girl being blindfolded, because it doesn’t show anything—it leaves a tremendous amount to the imagination. How did she get blindfolded? If anything, it invites exactly what you want, which is, curiosity. How did she get there? What happens from that point forward? I think that the cover served its purpose.

What did you look for, and find, in the young actors you cast? And in particular, what’d you look for, and find, in the lead actress? Because she really feels eerily perfectly cast—even though she’s older than the character in the novel, when I was reading the original novel afterward, I couldn’t help but imagine her. Her energy and presence was spot on.

In the original novel, the girl was very young. I believe she was 12 years old. So we knew, legally speaking, that I couldn’t cast a 12 year old and take a 12 year old actress, or actor, through that process. To me, even if it wasn’t illegal, it would have felt immoral. And one of the things that you have to do, which is something that’s usually not really spoken about, is that when you audition kids, particularly for this type of material, you have to audition the parents as well. And in auditioning kids, you want to first see if the kid can perform under these imaginary circumstances, but you want to also see how they deal with the material, and how the parents deal with the material—how comfortable they are, because they’re going to be on set. The parents were always invited and given full access to the set when their children were on set. With this type of material, you can’t have a closed door process, because you have the state labor unions, the Screen Actor’s Guild, and the parents, and everybody there is watching for the welfare of the children. For me, my primary purpose, after serving the story, was the protection of my actors, in regards to the material.

We casted with those parameters in mind, knowing that we needed kids that can act, and parents that will help us with the process of understanding. A lot of times, I would have to direct by asking a question, and the first question might be to the parents—”Have you ever spoken to them about child abuse?” And if the answer was yes, then I could have a dialogue with the actor about it. But if the parents had not spoken about it to them, then we would use more nebulous terms about pain or loss. With the other actress, who played the little sister who had suffered from polio, it was more, “Could you imagine what it would be like to lose a sister?”, that kind of thing, without going into the details of her abuse. The words ‘sex’ or ‘rape’ were never used—it was more about abuse, because they’re just too young to understand.

How much of the violence and inappropriate content was kept from the young actors during shooting?

What I did specifically was that, when there were particularly heavy abuse scenes, only the relevant actors were allowed. Usually, if it were a film about adults for example, I might have an adult actor behind the camera, viewing and seeing and interacting so that it can help the other actors in the performance of the scene, and it also helps with sense memory. But because I was dealing with children, I couldn’t do that—I didn’t want to do it that way, because I wanted to protect the kids. So it was more about establishing the kids in the room, and I would be avoiding certain words and imagery, and then I was literally directing them through their emotional reactions. And that’s how I directed them in the scenes.

And again, everything I was doing was done in conjunction with child labor laws, the parents, the unions—everybody was intimately involved in how I was directing these scenes. In particular, with the lead actress, Blythe, who I thought was fantastic, before we cast her, I talked to her and her agent in detail about how I was going to shoot certain scenes, shot by shot, image by image, to be as protective as possible.

What was the energy like on set? And in particular, what was the mood like during the shooting of the more harrowing scenes? How did you keep things from getting dour?

One of the ways you kept it light was by keeping around only the necessary people involved. When the kids weren’t there, they played around. There was a lot of camaraderie, a lot of bonding. And you kept it as light as possible without being disrespectful. So that was really it. The book was one of the most difficult books I’ve ever read in my life because it goes into so much detail, and when you read a book, you’re the director, so you can begin to imagine certain things, and it becomes really heavy.

So, remembering that, while I was on set, we actually had to go with the emotional opposite when we were between scenes—we’d let the kids go out and play and have fun. And again, in the way that I chose to direct them, I never made them go deep. That was my job, to go as deep as I could, with regard to characters and so on. And there were some cases where I had to switch characters around, with regard to the book, because there was some emotional difficulty that some of the younger actors were having. Once I sensed that, and discussed that with the parents, I’d let them know that I was going to rewrite the scene and swap characters and let the older character say a particular line, as opposed to the younger character. That way, it was never uncomfortable for them. I always kept a very open door with the parents.

Transparency was really the most important thing, and that’s what made it light. There were no secrets—the secrets were in the story itself, but not in the production.

The feel of this film is really quite fascinating. It almost has a Douglas Sirk quality, in that that visuals and setting and line readings and music feel deliciously idyllic-yet-fake at times, keying you into that you can’t really trust the surface of this world, and that there’s something sinister underneath. How did you set out to create the tone of the film?

Well that’s interesting you chose the word ‘fake’. That’s more in retrospect, meaning that, the facade we wanted to create was that everything is okay—this is a normal block, in a normal suburb, in post-World War II America, the 50s, a time of rebirth in America. Suburban America was very clean and above judgment, and so that was the facade that was created so that we could then go deep, literally and figuratively, into the basement, and into these characters. If you notice, we slowly bled color out of the film, the darker it got, particularly in the basement. And then at the end—which was completely different from the book, and something that I was very proud of that I rewrote—we brought color back, and we had the imagery of the river, where we see the reflection. In a sense, it’s almost a rebirth, so to speak. It’s come full circle. So that’s where the music and everything played into the calibrating of the emotion.

I grew up in the suburbs, so I can kind of relate to the idea of, ‘who knows what’s happening with my next door neighbor?’ You really don’t know what’s going on unless you’re there to see it.

Your second horror film, Ghoul, I haven’t seen yet, but I watched the trailer and it seems like the surface tone is a bit similar to The Girl Next Door, where things seem predictable and fake and too-good-to-be-true on the surface, and then there’s something sinister lurking under the surface—in the case of this film, an actual monster. Looking online, it appears some fans were up in arms over major changes to the story from the novel. What were you and the screenwriter’s goal with these changes?

Well, Ghoul was actually on [Chiller TV] again recently and it’s been on several times. When we premiered, it became the highest rated film in their history, at the time.

With regard to the changes, we made significant changes. I can understand why loyal Brian Keene fans were upset, and my reason for making the changes were very simple—while the book was fantastic, the book deals with a mythical creature that commits all these acts, and I won’t go too deep, but this creature also speaks english and does all these things that are very humanistic, and is very humanoid. And, when you think of the history of creatures or aliens in film that speak english, there are very few of them—maybe Predator, but his english was more mimicry than logical speaking, and it was never true dialogue, it was just repeating. And my statement was really simple to everyone—the network, Brian, and the producers involved. When they brought me in I said, if I do this, I have to make changes, and my reason was, when you’re the reader of a book, you can’t lie to yourself, because when you’re reading it, you’re imagining it, and your imagery can’t lie to you—and I don’t believe that this will translate as true in film form as it did in written form. Which they all got.

So I made significant changes with the writer, Bill Miller, and we let people know that there will be some surprises, and yes, there will be some changes, and I take full responsibility for the changes. I’m very proud of the film, and the film did very well.

Ghoul actually re-aired recently, the Saturday before Easter, and NBC Universal sent us an email saying how it did incredibly well, because they asked me to tweet along with the screening, making behind-the-scenes commentary. They said it was a huge success. I was very proud of the fact that they actually, on Easter Sunday, sent me an email, which was really great.

Truth is everything, and if you’re the filmmaker, it has to be true to you, and then you must translate it to make it true to the audience. So that was my approach, and I understand that some fans were going to protest—Brian Keene has a very rabid following.

Early on in your career, you interned on the film Apollo 13. How was that experience?

When I was at NYU, I secured the Universal Fellowship, and I interned directly under Lew Wasserman, who was the chairman and the last of the founding fathers of the studio system. I was interning directly under him, and while under him, I was allowed to float. One of the sets that I floated to was Apollo 13. And on the couple of days that I was there, it was really interesting, because they were giving classes, and when I say classes, they were giving the historical background on the capsule’s explosion, and they were really going into detail. They had people from NASA, and Jim Lovell was there. I had the chance to really just listen and hear the science behind how the capsule had the accident. And I was actually on the mission control sets, and I felt very privileged, because I was there listening and learning and watching people from NASA go into descriptive detail. It was great. It was a fantastic experience and I’ve always been deeply thankful to Mr. Wasserman and everything he did for me when I was out there.

That sounds incredible, yeah. This next question is one we try to ask everyone we interview, just out of our own curiosity. What’s your favorite film you’ve seen lately?

Lately. Wow. [Laughs] I’ve seen a lot, but one film that I really did like was Gravity, but that’s kind of easy to like. And for me it was very powerful, and plus it was science fiction, and I’ve always been a fan of space. So, that particular film I enjoyed very much because of the science, and because of the direction, and I think Sandra Bullock is really at the top of her game right now.

Lastly, I’ve been trying to track down a copy of your first film, Home Invaders, which has been quite difficult. I haven’t even been able to find a trailer. What’s been the hold up with its release? It sounds like an interesting premise, and it’s got a great cast—Keith David, Luis Guzmán, Larry Gilliard.

It had a distributor and there was a change in leadership. From what I understand, they went through some financial distress and they retained the film as an asset. And now I’m in the process of regaining the rights back so than I can have it released relatively soon.

Good to hear. Alright well, thank you so much, it was really great to talk to you.

Thanks so much. Thank you for the questions, they were great questions, and thank you for your time.

10 thoughts on “An Interview with Gregory Wilson, Director of ‘The Girl Next Door’”