Recently, WB announced their slate of superhero movies through 2019, perpetuating this ridiculous genre for another endless cycle. A lot of very smart people have been persistent in drawing an analogy about this, saying that for its longevity and frivolity, the superhero genre is the new western. As a lover of westerns and a hater of superhero movies, I gotta step in here.

I get the facile rationale—both are ‘low’ genres that occupy a disproportionately large space in the cinematic marketplace; both are marketed at American adolescent boys; both are concerned with matters of good and evil solved through third act duels. But in the words of Matt Zoller Seitz: “Where’s Ford and Leone?”

The western’s taken a lot of abuse over the years, but at its best, there’s a particular brand of artistry there that’s nowhere to be found in superhero movies. Speaking strictly of the classical western, the American run of films from the beginning of the sound era to the Vietnam war era—the John Wayne and Roy Rogers stuff—the heroism of the western is expressed in generalities, in metaphors, in an endless rolling landscape and mostly nameless characters. That’s why there are so few sequels in the classical western (though the Italian ones buck the trend in that regard). Superhero stuff, by contrast, is an encyclopedic expression of the very specific. Names are important—characters will often have two, one anchoring them to the world of their peers and one lifting them above it, emphasizing their particular combination of goals and abilities. Whereas the western is without overlap, a multiplicity of self-contained universes, the same experiment expressing itself over and over with slightly different results, the superhero stuff finds its distinction in one or two endless scrolling universes in which dozens of characters interact with one another in dozens of slightly different ways. Names, abilities, and slight personal distinctions are of paramount importance, a far cry from the western’s God’s eye sense of fable or folk song. You could never have a Man with No Name in the superhero genre—the storytelling falls apart at that scope.

The ironic thing is that this sense of the particular makes the superhero films more generic, while the generalized approach made the westerns something like a personal expression of something universal, a years-long conversation on the dominant cultural myth (that of the birth of a society through the intervention of an outsider with a gun) that was re-examined over and over and over with slight variation in perspective, so that the difference between a Ford western and an Anthony Mann western is the difference between those men’s personal ethics, their sense of what was possible in America.

It’s a shame to see the same stereotype that’s been around since their heyday a half-century ago: that the westerns were a select crop of A-pictures by exceptional filmmakers surrounded by a sea of crap. In my experience, nothing is farther from the truth—there’s a seemingly endless pool of great and near-great westerns just under the radar, films like Henry Hathaway’s powerful To The Last Man or Ray Milland’s A Man Alone or the unforgettable Hugo Fregonese film The Raid—all carving new paths through pretty much the same story. I’m not aware of that kind of small-scale personal storytelling in the superhero boom.

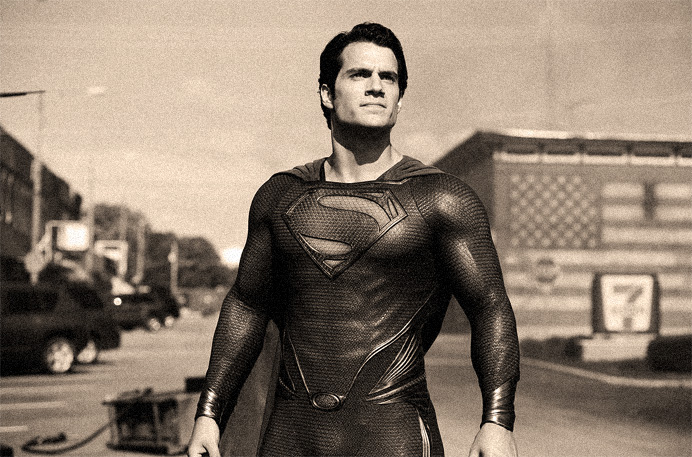

This is all stuff that I think is present in the comic books—Superman is famously bulletproof because Jerry Siegel’s father was shot to death in a robbery, and Spiderman is clearly geared to a new, skeptical generation—but the films are simply too big, too calculated, and too bogged down by demands for serialization to present any of that. The need to constantly make each film bigger than the last and to save the ‘true’ conflict for the third or the fourth outing is, to me, one of the defining hallmarks of the superhero genre and it’s something that is completely absent in any classical western that I’m aware of, including the serials of the 1930s and ‘40s which actually did have 10 or 12 sequels. This is the defining fork in the road, the structural change that means that, though both are low, adolescent, violent genres obsessed with good and evil, they’re philosophically miles apart. You can’t learn much about the future of the superhero genre by looking to the western. They’re not telling the same story after all.

But we’ve been here before. There is a genre that pioneered a lot of the storytelling in the superhero films: the sword and sandal films of the 50s and 60s. Here we see the same specificity, the same sense of a shared universe—Hercules meets Ulysses! Hercules and Ulysses meet Samson! Hercules meets Genghis Khan! Spinoffs galore—Samson got his own set of five films after breaking with Hercules. With a few exceptions (Fury of Achilles is very good) these are films of little visual distinction with bloated running times and impersonal stories, films of flat dialogue scenes occasionally disrupted by flabby, grappling hand-to-hand combat or contrived conspiracies (what up, Captain America 2). Much of the appeal was the thrill of new visual effects bringing to life beloved childhood heroes—El Cid in living color! An all-CGI Hulk! Even the terminology is the same: we’re promised “bigger epics” every year, just as we were in the early 1960s when the actual expanse of epics were brought to life. We even fret now over the fidelity of our ‘canon’, a Biblical term. Compare the outrage over a young, frail-looking Superman in Superman Returns with the famously lambasted “teen-idol Jesus” in King of Kings.

It’s not a perfect match, though—I’m not aware of an underclass of superhero films analogous to the Italian branch of the sword-and-sandal genre. Maybe it’s the television stuff like Gotham and Arrow, or indie superhero stuff like James Gunn’s Super, though there doesn’t seem to be very much of that. As far as things like WB’s slate, though, the AAA sword-and-sandals films are a much stronger point of comparison than the western, and their sudden demise after a few big budget bombs seem to be the logical conclusion to it all.

As for the western, that low genre of generality and repetition that told us so much about the American psyche, its heir apparent is already in the late stages of development. We traded the mythic endless frontier for the mythic endless city of cute brownstones and minimal traffic of the romantic comedy, the lonely gunfighter for the lonely yuppie in search of love. The romantic comedy, like the Western, reflects a lot of our cultural values and fears, and is home to some true artistry, despite near-universal dismissal beyond a select crop of A-pictures by exceptional filmmakers. Pretty Woman is closer to The Searchers than Batman Begins is, and the retreat of the genre into long-running television is exactly what happened to the western. How I Met Your Mother and The Office are the latest Bonanza and Wagon Train. I only hope in a half-century we won’t still deal with the pernicious stereotype that there’s nothing of quality to be found in the genre beyond the enshrined classics.