SLC Punk (1998)

Written & Directed by James Merendino

97 min.

I could never identify the groups in my high school. We certainly had some jocks, potheads, and even a few hanger-on goths. But punks, I don’t know. We had a kid with a mohawk; he was a fucking asshole. And we had a bunch of kids who loved punk music—a lot of them had safety pins in their clothes and dyed hair, but they seemed to really like some band called AFI, which I always thought was the American Film Institute. By the time I was in high school, punk music had completely soaked into the mainstream and everybody had heard of Pennywise and Bad Religion. It was in vogue to go see Henry Rollins do his spoken word shows in Ann Arbor, and if you were really cool, you already liked Bad Brains and Minor Threat.

I didn’t care about any of that stuff and I was tired of every local band sounding like Green Day. I was like the James Duval character in SLC Punk—the social diplomat. I could be friends with anybody. I was too busy getting into movies and figuring out my own depression to bother committing to some specific clique. Plus, the fashion of punk seemed so childish to me. It’s music; I don’t wear it, I listen to it. But that being said, we didn’t have nazis or rednecks either. Well, everywhere has rednecks, but our punks didn’t beat them with bats. Our punks were nice kids (except for that mohawked loser) and they got good grades and loved their parents. They went to Michigan State University and were proud to do so.

By the time I was in high school, punk was only fashion. But really, it always only was, even if you got beat up for doing it. I can’t relate to the universe of Salt Lake City as portrayed in James Merendino’s SLC Punk. But, on some level, I know those people. They’re familiar somehow. And it’s not because music and fashion are universal, or because we all grow up at some point, or any other Kumbaya shit. It’s because James Merendino wrote one of the best scripts in movie history.

My partner in crime back then was my best friend Rob. (I was probably more like Stevo, but he was no Bob.) And he and I would show each other movies. I showed him Star Wars and Rushmore and he showed me Three O’Clock High and The Wizard. I showed him Taxi Driver and Tremors and he showed me SLC Punk—a movie he watched everyday when he got home from school while eating hamburgers. I’m forever grateful.

SLC Punk fits right in to that heyday of post-Pulp Fiction, edgy independent cinema. From Trainspotting to Go we were constantly inundated with a barrage of gritty “indies”. Real festival darlings. SLC Punk is the good version of those movies. It’s everything you expect an indie to be: jagged, stylized, sardonic, funny, and filled with sex, drugs, and rock n’ roll—but it all serves a story. A beautiful story. While Go and Trainspotting and the like use style to mask their bland structure and shallow themes, SLC Punk is a reflection of youth; a rite-of-passage story and a hero’s journey.

The universe in SLC Punk feels real, and that reality comes from a cinematic synthesis of writing, performance, color, lighting, music, and sound—a culmination of elements that only a true master of the art form can wield. So let’s put it under the magnifying glass for a bit, because I want to understand why a movie I have no superficial connection to has such a profound effect on me.

Style is what amateurs use to impress, and pros use to express. SLC Punk is Annie Hall with balls. It’s a guy looking back on his life and analyzing it in order to find himself. The structure and point of view is exactly the same. I like Annie Hall a lot. I like that it’s actually a lot more stylized than people think, effortlessly going into subtitle jokes, cartoons, and continually breaking the fourth wall. SLC Punk utilizes the exact same style, but Lillard’s Stevo is a much more compelling chaperone than Alvy Singer. Alvy Singer never jumps up and down giving his parents the finger.

Stevo literally takes you on a tour of his life, immersing you in the hardcore punk scene of the mid 1980s. Throughout the film he continually breaks the fourth wall to explain the minutia of his everyday life, from the inner workings of the music scene, to his theories about anarchy and his station in life. His delivery is not only spot-on but wholly genuine. Lillard is a ball of energy and Merendino has essentially let him run rampant through his movie. Lillard knows how to use his entire body to express a line. It’s difficult to carry a movie, but I suspect it’s more difficult to literally yell at the audience. When he yells, he’s yelling at us, and when he’s sad, we’re sad. On the commentary, Merendino explains that during the acid trip scene he told Lillard that everyone on the crew thought he sucked. I saw the movie fifteen times before knowing that was the direction, but I could certainly feel where Stevo was.

Lillard leans into lines. His face contorts and his eyes widen and his mouth curls. He is the living epitome of the hyperbolic intensity that dominates the life of a fashionable, angst-ridden adolescent. Teenagers, especially outsiders, are inherently pretentious. They think the world begins and ends with them and Stevo is no different. I continue to be amazed at how earnestly the writing expresses this without overstepping. The movie uses pretension, like a woman starring into emptiness in the desert and waxing cheesily about that nothingness, to its advantage. It depicts the reality of teenage pretension so honestly that it allows itself to be as over the top as a teenager. This writing allows the pretension to be dramatically effective and resonant rather than laughable—which so many of its contemporaries are. (I’m looking at you, Prozac Nation.)

This clever use of pretension as a device is achieved not only through the writing and performances but also through a myriad of visual effects, “all of which I will gladly show you now”. (That’s a line from the movie.) The use of classical music enhances the self importance of the characters and exposes it without having to say it. But my favorite trick is the use of green screen. The foundation is laid early on when Lillard takes us on a tour of a party he and Bob have thrown. He shows us things and talks to the camera. But SLC Punk is about reflection. It’s a story told by a wiser man. There’s a brilliant scene when four characters are sitting at a diner talking about their future plans. Jason Segel is brilliant here as a punk who’s gonna go off to Notre Dame to study botany and save the rainforest. In a brilliant and hilarious character moment, he then clenches his fist and smashes it down on the table saying “somebody’s gotta fight!”. (Segel is a scene stealer even at 18.) What’s brilliant is that Stevo then turns to the camera to address us. He appears to be in the scene, but all of a sudden the camera starts zooming and Stevo remains frozen in place, still talking to us, as the sound of the scene dips lower and we realize the scene is going on behind him. He was shot in the scene but then through green screen trickery and matched lighting he is suddenly above the scene and talking about it. This kind of stylistic choice has to be incredibly deliberate because it requires a lot of planning to get right. Matching the lighting is tricky. This effect is proof positive that the style in SLC Punk is very much by design and done with a deep understanding of how the tools of the art form can be used expressively. Effects like that are unique to cinema. Playing with them is a beautiful expression of high filmmaking IQ. It’s what makes movies fun.

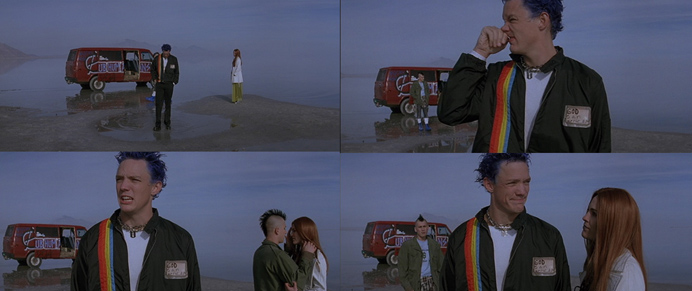

On the commentary, Merendino notes that all the jump cuts are not really a French New Wave nod, but just a lack of coverage. I suspect they’re neither and that he was just being modest. There’s a very meticulous design being exercised in SLC Punk that can’t be ignored. Not just in the camera and editing effects, but in the musical choices and writing, all the way down to the harsh, white highlights that populate the exacting and wonderful compositions. Interestingly, the movie was shot in 2:35, which is very wide. Merendino takes full advantage and uses many wide lenses, I suspect, to show the environments around the characters. Close ups can only be expressive if the information they contain serves the story. A wide shot can show you many things, and often a character’s juxtaposition to his or her environment is just as important. Also, the more you vary your shot sizes, the more impactful close ups and wide shots are by virtue of dynamic range. Think of all the jagged editing early on when Bob is ranting about drugs and compare that next to the very wide, single take shot later in the film when Stevo is hanging with Bob and Trish in the salt flats. The location itself is expressive and beautiful, but the shot size, composition, and blocking all express the drama.

Bob. What a great character. Don’t we all know a Bob? Not only is he the perfect compliment to Stevo, he’s also one of the most wholly likable characters ever put on film. There’s a great scene when Stevo is yelling at Bob. Stevo is mad and taking it out on his best friend, whom he’s jealous of for finding love and subsequently becoming less depressed and more together. Like most young rebels, Stevo naively thinks that Salt Lake City sucks—not realizing that you aren’t automatically cooler by living in New York City (the “hub and mecca of culture” as he calls it) in a brilliant diatribe to his parents. Lillard is acting his ass off in the scene, and during his angry rant we never even cut to the reverse for Bob’s reaction. Instead, after Stevo leaves the scene, Bob turns around to face the camera, revealing a very hurt friend. His face is like a knife to the heart, and with that one look, Michael A. Goorjian has stolen the entire movie.

There’s also a troupe of heavy-hitting character actors that routinely hit it out of the park, from the aforementioned James Duval and Jason Segel to the amazing Devon Sawa and the ever brilliant Christopher McDonald, who’s line “Fuck you, dear” is one of the most quotable in all movies. Til Schwieger is obviously a stand-out though. Not much can even be said about how fucking awesome he is in this movie.

There’s a great scene between Stevo and his dad where they’re sitting in Mcdonald’s sports car. Stevo, unlike Bob, is a rich kid; his dad is a well-off former hippie. Stevo has never faced adversity, apart from always being a nerd and an outcast. Bob is a punk because he’s searching for an identity in a world he doesn’t understand, whereas Stevo is a punk because he’s angry that the jocks gave him wedgies. The scene between Stevo and his Dad is very telling. Stevo takes every opportunity to take digs at his dads career choice, but it’s clear that the two have a rapport and understanding. This scene very intelligently telegraphs the trajectory of Stevo. The writing is very tender and smart and allows you, the audience, the opportunity to be seeded with the drama—the percolating confusion within Stevo. That scene foreshadows the inevitable ending.

The path of Stevo is incredibly fluid, especially for a movie with such a non-linear structure and a free form, stream-of-consciousness design. Take the Devon Sawa character, for example. Early on his role is purely anecdotal and universe-coloring. Bob tells a story about this kid who had a bunch of acid soak into his leg and it made him freak out and try to murder his parents. It’s the kind of story you hear growing up about the kid two towns over—all the details have been mangled by a gigantic game of gossipy telephone. But later in the film, Stevo encounters Sawa again, this time as a “fuckin’ beggar”. And although the lines are hilarious, there’s a very penetrating sadness that shapes Stevo’s arc. This kind of clever positioning of elements, this set up and payoff, is a very advanced and mature brand of writing that cannot be ignored.

Finally, in one of the most profound moments in movie history, Stevo makes his closing statements. He was a poser all along, and they all were. It’s impossible not to be. What follows is one of the sweetest things ever put on film. The sentiment rings true, and the scene with young Bob and Stevo encompasses the beauty of life: sharing art with your friends in your adolescence might be the best thing you ever get to do. I’m certainly glad my best friend Rob shared SLC Punk with me.

1 out of 1 stars.

Did you always want to be a filmmaker, how did you get you start?

I always wanted to make movies. That or Botany. I got my start making Lord Of The Rings in the forest and hills behind my house when I was 11. All shot on Super 8.

How much of SLC Punk is based on your own experience? I’m very curious to hear about the journey that lead you to this movie. It’s kind of a real rags to riches, American dream kind of story if you think about it?

Is it? I would think Riches to Rags. Stevo’s a spoiled rich kid. He’s kind of like Francis of Assisi. But the story is rather personal. It was not meant to represent any scene. Just a reflection on myself and my outsider friends. There were and are much cooler Punks in SLC than me. I set out to make a movie about my generation of outsiders. When I went out with the script, Hollywood was outraged by it. Baby boomers said, “Your generation didn’t stop a war. Who cares about you.” I was surprised by the reaction. So I went to Germans for the financing. Hollywood doesn’t like this movie. There’s no clear happy ending.

On the commentary you say the movie was shot for $800,000. How’d you get the money? You mention that Jan De Bont was involved.

If I said 800K it was a lie. It cost 2 million. Jan was the only ‘Hollywood’ person that understood it. But then again, he’s Dutch. So he was not intimidated by the subculture. It didn’t challenge him or threaten him. So he lent his name to the effort.

How’d you get the cast together?

We auditioned a lot of actors.

What was sundance like back in 98?

I grew up skiing in Utah. Sundance is always Sundance. One week a year it is filled with Industry folk screaming into cell phones. The shape of the phones have changed. That’s all.

What were some reactions from the cast and people in your life who saw it? On the commentary Lillard seems to be very happy with it. Was that the case with everyone?

I don’t know. I assumed everybody hated it.

In the last ten years, SLC Punk has gone on to be a pretty polarizing cult classic. By the time I was in high school in the early 2000’s, it was already the bible for many of the punker kids. How does that make you feel, to have made something that many people really remember and cherish?

“Polarizing”. As in a movie that divides people. I think people may have taken it the wrong way. But if people cherish the movie, well that’s great. But if it has become a religion, that’s very, very bad. Because it’s just my story. I did not mean to preach or suggest I represent ‘Punk’.

I want to ask some questions about some things I mentioned in the review. You say on the commentary that the jump cutting was done out of necessity. I presumptuously put out that they were design, so here is your chance to prove me wrong.

I didn’t have time for coverage. So, like the French New Wave directors, I used the jump cut trick. But once you commit to that, it becomes a design. It has to, or the movie falls apart. You have to do it with purpose, or it seems unnecessary. I try to use all my money limitations to my benefit and make those solutions become necessary to the style of the movie. Example: you want to make a horror movie. You have five thousand dollars. What to do? Pretend the movie was shot by the characters in the movie with a cheap camera. Now the poor quality of the movie is a necessary part of the movie.

Along those lines, there is a lot of design in the effects shots, from the acid burning into Devon Sawa’s legs to the speed ramps, lighting gags, and green screen effects. Did you visualize these moments? Can you discuss in detail how you worked some of these out? I’m curious because it’s not just that these moments are ahead of their time but that they are things that not many people have ever even tried to do so I’d love to hear about their inspiration and ultimate executing.

Those things were in the script. Once you have a moment in a movie that requires a visual effect, it doesn’t take much FX acumen to sort it out. You put up a green screen, shoot your foreground action. Take it away and shoot the BG. I like ‘in-camera’ effects. So I compel my production Designer to build the duplicate of the corner of a fifth story apartment in a house. So when I shoot the scene starting in the apartment. I can dolly left and follow the actor right into a different location. I wanted to do these things to really separate Stevo from the story and support his role as the guy selling you a story.

Was there any special reason for shooting in 2.35:1? Was it difficult to light and shoot on such a small budget?

I love anamorphic. I like the frame. It does not take any extra lighting. Or special lighting. You just need brighter lights because anamorphic lens’ do better at higher f-stop concerning focus.

The lighting and compositions are both very expressive and deliberate. The lighting is often very harsh and the compositions and camera movements are big. There’s a great mixture of big wide shots and intimate, handheld shots. Talk about that a little. How closely did you work with you DP? What movies inspired the look?

I like contrast and I want to burn the image into the film. I also think it’s important to be ambitious and open up a picture, visually. I want to see the world they inhabit from God’s POV and I also want to see it from their POV. So I switch back and forth depending on what feels right. I do not follow any rule as in wide, two shot, CU.

You’ve announced a sequel to SLC Punk. What can you tell us about it right now and what inspired you to go back and mine the material?

As I said, SLC Punk was a very personal story. I tell all kinds of stories. But if I am going to talk about my observations as a Gen X outsider, the medium and style that SLC Punk was set in is the medium I feel comfortable working in to talk about me. I invented that medium for this purpose. A sequel is misleading. It’s just what I do. I use these characters and this style with this humor to express what my friends and I, or people I know, think and do. Once again, Hollywood is rather hostile to this subject. They are baby boomers or are following the rules of Baby boomers. They don’t want to know about my outsider generation at any age. They don’t understand the problems we face in our late 30’s. They don’t even want to. If it’s not This is 40 and all about your money and babies and sex problems, it’s irrelevant. So I’m twisting arms.

What’s your favorite movie?

Really?

What’s your least favorite?

Really?

Awesome.

I agree with rob. This is an awesome interview/review.

really lol