Cría Cuervos (1976)

Written and Directed by Carlos Saura

110 min.

Very mild spoilers ahead.

When I was seven, my mom made a home movie of me walking around a mulberry bush surrounded by purple and white flowers, picking them and humming to myself quietly. Even though I had bossed her incessantly before she hit record to follow me with the camera as I carefully timed my pauses and expressions, she did what moms in the 90’s with fanny packs and Hi-8 cameras did instead—she began to narrate it in the most sarcastic, dorky voice possible: “This… is… Chloe…”

At the time, I didn’t know that I was trying to direct. I didn’t even know what directing was, nor had the concept of moviemaking ever occurred to me. And to this day, although I want to make movies, I haven’t done anything serious—I’ve only been daydreaming, just as I had been doing on that day, when her seemingly oblivious voice interrupted me and made me feel embarrassment that I’d been caught, and as though a special moment had been robbed of me. I angrily ran up to her and yelled at the camera, “Mom, erase it! Erase it!”

My mom must not have been as oblivious as she acted though, because after that, she made our main way of interacting watching and analyzing movies together. And she instilled in me, not just a love for movies, but a certain idealism about life that has stubbornly remained and kept me alive to this day, long after she’s been gone.

One might assume that it’s easier to write about movies that strike us deeply in our souls. However, this is the most challenging piece I have ever written—not because I have little to say about the film (I have so much to say about it) but because it takes a lot of discipline not to go on and on about my entire life story over the course of explaining why I was so deeply affected by it. Cría Cuervos is basically a movie about my childhood—and the reason I watched it was that someone who knows me very well said, “Watch Cría Cuervos, it’s the most Chloe movie ever.” They were right—I had to pause it several times in order to not blur the frames with my tears.

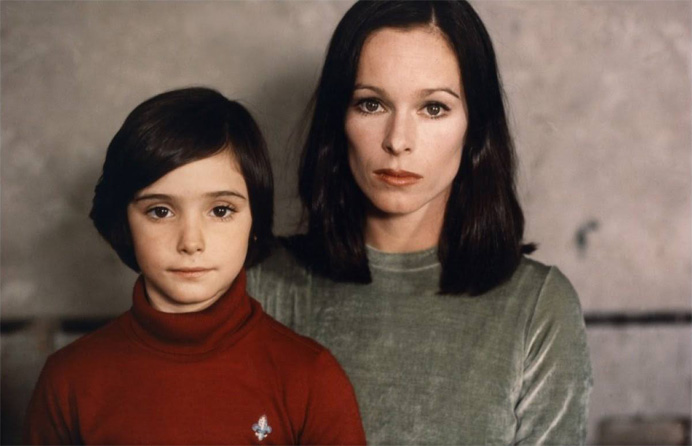

I’d say that the amount I relate to the story creates bias in whether or not I can actually tell if it’s a good movie—if it weren’t for how beautifully shot, lit, scored, costumed, and acted it is. It stars Ana Torrent (a little girl at the time, though sure doesn’t act like it) and Geraldine Chaplin, who plays both the girl’s adult self and her mother (a very clever choice expressing the child’s very relatable fascination with the beauty of her mother, yet fear of becoming her, all in one visual stroke, without ever needing to be mentioned).

I first saw Geraldine Chaplin playing her own grandmother in the Chaplin biopic many years ago. Her performance in it stood out to me enough that I became very curious about Charlie Chaplin’s relationship with his mother, leading to me reading his autobiographies and watching all of his films. It didn’t take long for me to realize that I didn’t care much for the biopic after that, but my love for Chaplin’s life and work remain—he was my first introduction to not only the concept of an auteur, but to an artist that had been through a traumatic childhood similar to mine (and also similar to what Ana goes through in Cría Cuervos). So it’s a pretty neat coincidence that Geraldine is in it, and I’m very impressed that her performance here is much more realistic than it is in Chaplin.

It isn’t so much the fact the the movie is about Ana coping with her mother’s illness and death that I relate to, but the similarities in how she copes—and it is this aspect that should make the film powerful to anyone, whether they’ve had traumatic childhoods or not. There are truths to be found here about the perspectives of children that are universal, and this is the first film I’ve seen that portrays them so clearly.

The most prominent coping mechanism illustrated in the film is daydreaming. Although Ana’s face—with her bobbed hair, blowing in the wind, and her expressions of apathy, wonder, and determination—bring to mind scenes from Miyazaki (which is impressive, because this is live action, and Spanish) nothing particularly surreal happens in the film. However, about half of it takes place in daydreams, and has the subtle vibe of such. These daydreams are her way of coping with loss—by simulating the presence of her deceased mother—as well as her way of escaping pain and obligation. This theme is explored so deeply and effectively (without ever being spelled out, my favorite) that we are even shown what happens when such a coping mechanism no longer works—as well as when reality closely resembles the daydream, yet incorrectly, upsetting the daydreamer.

It isn’t only the loss of her mom that she’s coping with though—it’s the loss of an idyllic way of life that she feels was promised to her, but never received. When we are very young, we go through a time when the only influence we have on us is our parents, and although we are scared and uncertain, we trust them and allow them to build a schema of a world that is ‘correct’. If something happens to a parent that is out of anyone’s control—say, a mental and/or physical illness—a sort of contradiction occurs where, while the world they created is shattering—along with them—we are stubbornly holding fast to the ideals and habits they instilled in us, because they are all we know. The only way for this to work is to be in a sort of denial—hence the daydreaming—and when this denial is threatened by new caregivers trying to rewrite the parent’s schema—say, by trying to establish new rules and routines—the child becomes unbearably rebellious. This is why, so often, Ana behaves coldly, and more adult than most adults, yet expresses openly the irrational desire for everyone around her to die.

I remember feeling all of this as a child, and even looking and moving as she did, doing many of the other things she does in the film, such as listening to a song, over and over, in solitude. And I love the way that the harshness of this character differs from the usual portrayal of children coping with loss in film. Usually, we see too much emotion from them, as they cry, scream, or act obnoxiously creepy. The beauty of Ana Torrent’s performance is that she is stoic. Instead of having facial expressions and words shoved down our throats, we simply see what she sees. We become the child, which treats the character with just as much respect as an adult, allowing us to take them seriously.

Sometimes the film breaks the fourth wall, as though she’s aware she’s in a film. The way she occasionally looks into the camera acknowledges that she is aware she is daydreaming. These scenes have warmer colors, and she is in closeup, centered by the frame. By contrast, the scenes that take place in reality are shot wider, the colors cooler, as she silently observes adults behaving in negative ways towards one another. I think this is what life feels like to young filmmakers before they know they’re filmmakers—as I stated before, daydreaming is filmmaking, before we know what filmmaking is.

The comforting nature of a daydream, as a coping mechanism in life, puts us in the center of our own universe—but, if overused, it has the danger of making us feel like we unjustly deserve fawning praise and recognition, not only for having survived our traumas, but for constructing beautiful images privately in our own minds about them. If we become too absorbed by this, we develop into narcissists who simply wish we were filmmakers, never actually becoming filmmakers at all—much as I haven’t yet. We take the child in us too seriously, and are at risk of becoming like Caden Cotard, the frustrated artist protagonist of a similarly daydream-themed film, Synecdoche New York.

For a long time, I thought that my childhood would end up being the subject matter of my filmmaking, but I now realize that obsessing over this holds me back from expressing something new. So, while Cría Cuervos hits really close to home, it is only ‘the most Chloe movie ever’ for my life up until now—the movie I needed to see in order to finally put my mom’s ghost to rest, learn to cool it a little with the daydreaming, and use my creative energy towards finally actually making stuff.

You are fantastic! I love you!

I know your Mom would be so proud of you. If all of your writing is anything like this example you are well on your way to impressing a lot of people. First of all you make me want to see Cria Cuervos. Your observations and insights are expressed so well that it truly shows how much you have learned about life in such a short time. I know that you had some unbelievably hard times trying to deal with what was happening to your Mom, but apparently it sounds like you have figured out how to cope and move on. I can’t wait to see the great things to come as you use all your creative talents. You know that you are more wise at 24 than most people I know who are my age. I love you so much and I am so impressed. And it’s not just because I’m your aunt!

You’re an extremely talented writer. A really touching piece, Chloe.