When I was in junior high school, Scarface was the most talked about movie in the hallways. It was 2000, and those hallways were a reflection of the culture at large. One time a kid asked me, “Who directed Scarface, Scorsese?” He had never heard of Brian De Palma.

There’s a popular book called Easy Riders, Raging Bulls. It’s a gossipy, oral history of 60s and 70s American movies. In the back of the book, they summarize the directors integral to the movement and give a filmography for each. Spielberg, Coppola, Scorsese, Lucas, and Malick are featured, but not Brian De Palma—despite being mentioned heavily in the book. You’d think the guy that gave Robert De Niro his first on-screen appearance (The Wedding Party, 1969) and gave him steady work way before Scorsese ever did, would be important enough to mention.

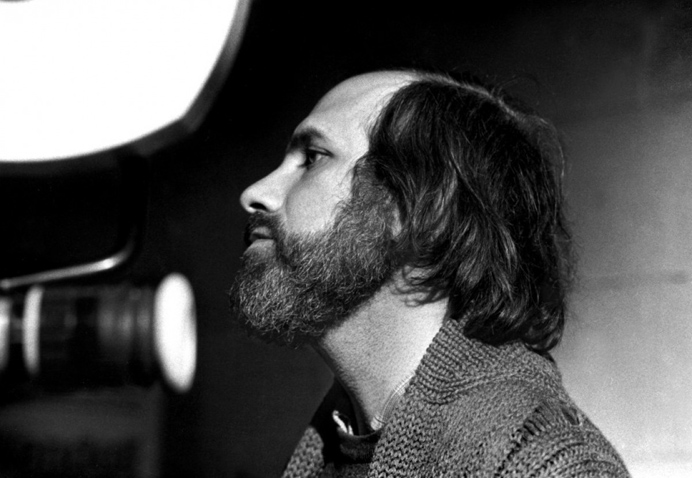

Brian De Palma’s work is so important and vastly interesting that I don’t even really know where to start, so I’ll just start with his best movie: Carlito’s Way.

Brian De Palma is an awful screenwriter. Just awful. Raising Cain, Body Double, and Redacted are the best evidence of this. The ending to Raising Cain is so absurdly stupid that I can’t even talk about it. All De Palma’s scripts are basically melodramatic and cheese-ridden. His dialogue is corny, his characters are mindless and one-dimensional, and his plot devices are ludicrous. His best movies are the ones he didn’t write.

Carlito’s Way was based on a book and adapted by David Koepp. Koepp’s resume was looking good in 1993—he had just adapted this book called Jurassic Park for De Palma’s best friend.

This film also marks the ten-year reunion of Scarface, and is De Palma’s other mafia movie that stars Al Pacino as a bombastic weirdo with a crazy accent.

Carlito’s Way informed the 90s aesthetic just as much as Goodfellas. The saturated red lighting, retro 70s chic, and kinetic style are as much the informer to Boogie Nights and The Sopranos as anything else. Sean Penn’s Oscar loss for Best Supporting Actor is criminal, and the entire cast is phenomenal.

This movie succeeds where his other work fails. David Koepp’s cheese is poetic rather than stupid and De Palma’s execution is equally lyrical. It opens with post-production slow motion (i.e., slow motion done in the editing room rather than in camera—this, smartly, achieves a blurred motion that looks dreamy) and black and white photography tinted a bluish purple. The sequence is from Pacino’s point of view and the camera floats across the action. There are few better depictions of a man who just died. In fact, I can’t think of any.

As you’ll see though, De Palma’s filmography is littered with cheese. A veritable cinematic rat trap. But it’s a trap that I love to be caught in.

What De Palma does well are all the things good directors should do well, but don’t. He knows how to use a camera to make you feel things. Tarantino does this too, and is a better writer (sometimes). The reason Tarantino’s movies look awesome, and more importantly, feel awesome, is because he fucking loves Brian De Palma.

Occasionally, Tarantino uses something called a split diopter lens. This allows subjects very, very close to the camera to appear in focus as well as subjects very far away. By virtue of watching movies, our brains have been wired to how a camera lens sees things, which is very different than our eyes. Not only is there an arbitrary ‘frame’ but there are different lenses that put the background in focus or out of focus, flatten the image, widen it, etc. Our brains have built up acceptance of these lenses because we’ve been inundated with so much media that we just kinda get how they work without thinking about it.

A split diopter lens purposefully jogs our senses. We aren’t used to seeing things like that, because the grammar of cinema and the technical tools used to execute them have cultivated a set of rules that our brans follow. The best, most advanced directors subliminally deviate from these rules ever so slightly to evoke feelings in us.

Many filmmakers besides Tarantino use split diopter lenses. Hell, there’s even one in an episode of Freaks and Geeks. But nobody has quite like De Palma. Just look at how he uses it in Dressed to Kill, as opposed to how Tarantino uses it in Pulp Fiction:

(These were the best quality screenshots I could find. When I find better ones, I’ll replace them.)

Now onto his other movies. Mission Impossible sucks. It’s fuckin’ weird and long and boring. But there’s that scene. You know the one I’m talking about, because it’s the only scene that matters. Incidentally, it’s a scene that Spielberg did better in Jurassic Park 2, the most forgettable movie of all time (after Knocked Up).

There should be a name for the phenomenon where when a movie is played ad nauseum on TV, you will invariably ALWAYS land on the exact same spot no matter what time of day it is. I like to think it’s the universe telling us all what the only important part of the movie is.

I defy you to tell me you’ve ever landed anywhere in Mission Impossible other than the Tom Cruise hanging from the ceiling scene.

Anyway, it’s a great scene. It has a built-in tension, which is what De Palma does best. That’s about all I have to say about the movie. Hold on, though—before I go through his other movies, I have to talk about something important.

I’ve been talking about how De Palma informed Tarantino, about how Tarantino took the ball and ran with it and made himself more famous, and good on him for doing so. He’s the Barry Sanders of American movies, and De Palma is the Joe Montana or something.

But I can’t talk about De Palma without talking about who he got the ball from. If you’re ahead of me, then you’re a movie nerd like me. Alfred Hitchcock.

If it’s 1960, Alfred Hitchcock (and Orson Wells) is the best filmmaker of all time. He’s one of the only guys pre-1970 to do anything remotely interesting. Not that interesting, though. I mean, his movies are boring as fuck. But hey, they were made at a time when people really didn’t know any better. “Hey this painting looks like the sky right?” “Yep, it’s like we’re outside! Movie magic!” (It’s insane to me how fake driving in cars still looks here in the future.)

De Palma does Hitchcock better than Hitchcock. To think otherwise is to kid yourself that Hitchcock is good simply because he did it first. He’s interesting perhaps, but not good. In fact, De Palma’s cheese kind of exposes Hitchcock’s inherent badness, and goodness, all at once. Hitchcock is advanced because he was one of the first directors to create tone on top of the story, which is where the movie is. Before him, it was all just nuts and bolts. Hitchcock uses composition, camera movement, and music, all in synthesis, to deliver information in a way that helps the audience feel tension. De Palma’s movies do this with more effectiveness because he learned from the only master before him. You don’t need to see Hitchcock to get it, because the DNA is in De Palma. Like any trailblazer, he stole from the best, and took it further. (Sound familiar? Tarantino.)

Not only is De Palma better than Hitchcock, he has a more interesting filmography. What people don’t really seem to understand, or care about, about De Palma, is how insane his filmography really is. He’s done it all: blockbusters, iconic horror, Joe Piscopo vehicles, avant-garde underground films, horrible sci-fi movies, Scarface, famous flops starring Tom Hanks, and many more.

Let’s start with his early movies though. De Palma’s early movies are fuckin’ weird. I can’t wait to talk about them!

Brian De Palma is a science geek that grew up in a dysfunctional, broken home (as semi-depicted by Keith Gordon’s character in Home Movies and Dressed to Kill). He was born on September 11th in 1940 in Newark, New Jersey, and made his first movie, Icarus, in 1960, and continued to make nine movies throughout the decade. Many of them are extremely rare and underground. I was able to see a few of them while living in NY and having a membership at the famous Kim’s Video.

Like every director, his early films are just practice. They aren’t good or groundbreaking but merely proof that the director can pull some things together and put some ideas on screen. This achievement is all the more impressive in the early 60s, forty years before digital cameras made it so that everybody ever could be a ‘filmmaker’. So they’re great to watch and study what it meant to be a budding filmmaker so long ago.

I haven’t seen them all. I’d fucking love to see Show Me a Strong Town and I’ll Show You a Strong Bank (1966) or 660124: The Story of an IBM Card (1961) but not even Kim’s had those.

I was fortunate enough to see Woton’s Wake, which is his first teaming with actor William Finley, a partnership that would extend to 6 movies (Dionysus in ’69, Sisters, Phantom of the Paradise, The Fury, Dressed to Kill, and The Black Dahlia).

Woton’s Wake is a cartoonish, sardonic, comedy about a sort of mad scientist that kinda just wreaks havoc and does weird things for about 20 minutes. It’s 16 mm, black and white, shot on high contrast reversal stock, and looks like pretty much every other promising student film. It’s boring, nonsensical, but shows a certain visual prowess and spark that was fortunately allowed to foster and develop. Wake was scored by Finely, which I suspect informed their working relationship over the next ten years or so.

In 1969, De Palma filmed Dinoysus in ’69, a very bohemian, experimental Village play starring Finley. It was an audience-interactive ‘experience’ incorporating a lot of movement and nudity. It’s basically about 90 minutes of chanting and nothingness that culminates in Finley declaring himself a leader or something, and launching into a faux political rally rant.

De Palma filmed the entire play with two cameras and used split screen for the entire 90 minutes, showing both the audience and play simultaneously. As you can imagine, it’s mind numbing, but it predates Woodstock and is actually a pretty interesting use of split screen, albeit a cinematic dead-end.

I was born in 1986, so as much as I can take an interest in other cultures and time periods, I’ll never really know what was going on. However, from what I’ve garnered from being inundated with mod, British pop, and rhythm and blues from a super hip mom that would show me Help! and A Hard Day’s Night ad nauseum before the age of 5, I can tell you, with my limited expertise, that Greetings, and its sequel Hi Mom!, are a picture of the 1960s.

Greetings is a subversive, draft dodging, fuck you to authority, filled with sex, artistic experimentation, colors, drugs, and crappy guitar music. ‘Art films’ today are so plastic and homogenized that it’s hard to imagine a time when a filmmaker just took to the streets and threw together some colorful nonsense and called it a movie. Greetings isn’t great, in fact it’s not even that good. It is, however, a time capsule of an energetic period when art was somehow ‘important’, and an extension of a changing cultural zeitgeist. Greetings may ultimately be a big hodgepodge of nonsense, but so was that kooky decade, and few movies capture that with more heart and integrity. It’s a shame that lesser works like Easy Rider and Head get all the attention.

Hi Mom!, the 1970 follow up to Greetings, is better—still not great, but a lot better. De Niro’s work in Greetings and Hi Mom! shows the first signs of promise in an actor that would later see his range sucked away by typecasting and comfortability. Don’t get me wrong, De Niro is great, but even in the comedies like Analyze This and Meet the Parents he’s being funny based on his schtick—it’s not really an extension of his talent. The King of Comedy, The Mission and Brazil are perhaps the only roles that showcase his other chops, and those chops are subtly telegraphed in Greetings and Hi Mom!. In both, De Niro plays the straight man in a zany world of paranoia and sex. He anchors the nonsense and basically carries the movies.

Although Greetings and Hi Mom! are disjointed at best, often times launching into non-sequitur vignettes only bound by thematic coherence, there is one sequence in particular that is truly transcendent. Hi Mom! has a subplot (if you can call it that) featuring an underground performance art group called Be Black Baby. Their portion of Hi, Mom! is a black and white sequence that heralds the advent of the found footage genre that would come into popularity some 30 years later. The group recreates the black experience by using experiential theater to essentially taunt and terrorize a group of white people, their audience.

De Palma uses a handheld camera to put you in the room, a style that has been so done to death that it’s easy to forget its effectiveness. The difference here is that at the time, news and fly-on-the-wall footage really did look like that (another good example being the battle scenes in Dr. Strangelove which were similarly photographed by Kubrick).

As the scene begins, you never suspect its inevitable outcome, and the tension rises as the lines between safety and reality get blurred. What’s impressive here is that De Palma is able to use a combination of performance and editing to create the tension. The sheer idea of suspension of disbelief fades away because De Palma is manipulating the tools of cinema before your eyes. This is a level of sophistication far beyond its years, and much more transcendent than anything in any Hitchcock movie.

De Palma’s follow up to Hi, Mom! is almost completely unknown. Get to Know Your Rabbit, a Smothers Brothers vehicle featuring Orson Welles. The film was taken over by the Smothers Brothers, which De Palma sites as its undoing, however I suspect the movie wouldn’t have been very good regardless. It’s pretty boring and forgettable—really only interesting as an obscure piece of history.

Sisters, which was confusingly remade in the 2000’s, is perhaps the beginnings of De Palma’s stake in cinema history. Sisters can convincingly be referred to as a cult classic by the Fangoria crowd. And deservedly so. It’s boring and confusing (are you noticing a trend?) but it marks the first time that De Palma’s stylistic universe met critical mass.

Dionysus in 69 is worth its crappiness, if for nothing more than the fact that it primed De Palma for one of the most brilliant split screen sequences in movie history. The truth is, split screen has barely ever been used well in movies. If the world made more sense, what De Palma started would have been picked up by somebody else and ran with (like he did with Hitchcock). Instead, styles changed, and nobody ever came along and made a better De Palma movie than De Palma. But it’s simple really, the scene in Sisters. I don’t want to give it away, but the components are simple. Something happens that cannot be seen lest our character get into trouble. Somebody is about to see it. These two ideas are run simultaneously in splitscreen. Again, pretty simple, but how many times have you seen it? Watch the movie and revel at its thrilling choreography, brilliantly staged by De Palma (all the way back in 1973, no less). It’s a scene like this that allows you to truly see into the mind of an auteur. Only somebody with an extremely high cinematic IQ could design a sequence like that, because it requires thinking beyond traditional staging. It comes from an innate ability to intuit the movies you’ve seen and design new ones organically.

His follow up, Phantom of the Paradise, is a bonafide cult classic. Finley gives a tender, human performance that showcases his songwriting and vocal ability in what is one of the weirdest movies ever made. Eraserhead is weird. Eraserhead is blatantly weird. Its weirdness is superficial and intentional. Phantom of the Paradise is just fucking weird. It’s got Paul Williams as a dude named Swan who’s like this diabolical, villainy music producer guy. And there’s a whole section where Finley is wearing this crazy helmet that makes his voice sound all static-y.

Obsession is perhaps De Palma’s most overlooked picture. A De Palma movie is always an event in some way. Whether it be a famous flop like Bonfire of the Vanities or a beloved classic like Scarface, there’s always something spinning around its periphery that makes it seem larger than life. But Obsession is just kind of ‘there’. Maybe it’s because nobody cares about Cliff Robertson. Obsession however marks De Palmas first time working with John Lithgow, who’s awesome as the movies slimy shitheel. It also features one of De Palma’s most dazzling endings, which I won’t spoil here since you most likely haven’t seen it. What’s perhaps most notable about Obsession is that it is his first blatant Hitchcock movie.

It’s 1976 and we’ve now arrived at De Palma’s first iconic movie, Carrie. Carrie is the first of De Palma’s movies that we’ve all seen, and is part of our culture. It’s interesting to look back on a time when Carrie was a teen movie. The teen movies of the 90s didn’t open with a graphic nude school shower scene where a girl is essentially tortured by her classmates for having her first period. I really like the part when the camera spins around Carrie and her dance partner at the prom, and it just keeps spinning faster and faster. And I love that PJ Soles is in it. And who knows, would Stephen King have had such a hot career if not for De Palma? Think about it

In 1978 he made a really shitty movie called The Fury with Kirk Douglas.

The 80s were De Palma’s best decade. Beginning with his most outward Hitchcock homage, Dressed to Kill. Dressed to Kill is kind of awesome. The sequence in the art museum is just that—awesome. Dressed to Kill opens with some boobs, and then has Angie Dickenson getting ‘made love to’ on a bed. She’s faking it, the guy is clueless, and De Palma has arrived. Dressed to Kill is what we think of when we think of Brian De Palma, if such a thing can be said about a guy nobody thinks of. He is the most anonymous auteur with the most flashy and identifiable style.

The museum sequence is so dripping with De Palma you just have to see it. From the moving, intentional POV camera to the fade-in memory bubble on the right side of the screen, it just screams “I make movies, look at me use movie tools!”

The rest of the movie is kind of whatever, but I think what’s interesting later is the Keith Gordon character. He represents the young De Palma who would spy on his father having affairs. He’s an innovative young nerd, clever with gadgetry. There’s a scene where he whips up a kind of camera thing to spy on some dude. He’s building it in his room but the set looks like some kind of dark scientist lair. This is perhaps the most honest and human reflection of De Palma that we get throughout his career.

Incidentally, his next film, Home Movies, is unabashedly his most open because it is an autobiographical account of his formative years. With, you guessed it, Keith Gordon playing him. Home Movies, in classic De Palma form, is very odd. It is framed with Kirk Douglas bombastically lecturing a small group of film students as a comically cartoonish huckster. Think the Robert McKee character in Adaptation, but played by Kirk Douglas, so even more awesome. Douglas introduces a series of extended vignettes that tell about a put upon teenager and his dysfunctional home life. What’s most interesting about the film however is that it was made by a class that De Palma was teaching at Sarah Lawrence. The students fulfilled all of the technical roles and co-wrote and produced the movie alongside De Palma. It’s kind of a shame that A) there is no documentary of this—had it been made twenty years later their surely would have been—and B) that this film is not more widely known—not that it’s a great movie or anything, but it’s certainly interesting.

Blow Out is also weird. Famously it is one of Quentin Tarantino’s three favorite movies, the other two being Taxi Driver and Rio Bravo. Blow Out is strange because thirteen years previous Antonioni made a movie called Blow Up, that was the exact same movie but instead was about a guy who takes photographs and it ends with a weird mime game of tennis. In De Palma’s version, it’s about a sound recordist and ends really cheesily—in classic De Palma fashion. Blow Out it undoubtedly better than Blow Up because De Palma is better with the visuals and not boring. There’s a really cool sequence where the camera keeps doing 360’s around the room, filmed at a lower frame rate, while Travolta works on his sound stuff. I suspect that if it weren’t for Blow Out, Travolta never would’ve wound up in Pulp Fiction. And De Palma got a pretty good performance out of him (he had worked with him previously in Carrie).

Scarface is next, but there’s isn’t much to say about Scarface that hasn’t already been said.

As I said at the beginning of this essay, it’s unfortunate that the culture that loves this film forgot about its director. For whatever reason, when people care about The Godfather they care about Francis Ford Coppola, and when they care about Goodfellas they care about Martin Scorsese. Nobody who cares about Scarface cares about De Palma, and there’s really no reason for it. If you go film by film, comparing these three directors’ respective filmographies, none of them really outshine each other.

Ultimately, De Palma falls out of favor for trying to make movies people actually like. Apocalypse Now is a popular movie, but it’s also a three hour long avant garde art film masquerading as a war movie. And Scorsese made fucking Kundun. De Palma has his share of clunkers, but I think ultimately the people that bought tickets to Mission Impossible just don’t care about who made it. And the people that do care about who makes a thing don’t care about Mission Impossible, so it’s an unfortunate catch 22 that leaves an artist toiling in obscurity while Scorsese gets pity oscars for mediocre movies like The Departed, presented to him by Lucas and Coppola, while De Palma is probably watching from home.

Body Double ties Dressed to Kill as his most Hitchcockian outing. Rear Window is the one being redone here. I guess if you care about Melanie Griffith for whatever reason, you might care about Body Double. At this point it almost feels like a stupid thing say, but you could say that Body Double is Brian De Palma’s most De Palma-esque movie. The story is stupid and barely makes sense at all. It’s visually captivating and fun by way of amazing visuals, tension, sex and colors. It’s all you could ever hope for from him!

Here’s a really weird thought. Goodfellas couldn’t be called Wise Guys, even though it obviously should’ve been (that’s what the book is called) and you even get the sense that the narration when he says “we were wise guys, we’d say you’ll like this guy, he’s a good fella.” it’s tacked on. Goodfellas is clearly an invented word to make up for the fact that four years previous, Brian De Palma made an insanely unfunny Joe Piscopo vehicle featuring Danny DeVito called Wise Guys. Movie fuckin’ sucks.

I think De Palma’s obsession with cheese is concurrent with his eagerness to please audiences. I think he’s ahead of them as an artist, but behind them as a purveyor of ideas. I think he thinks cheese is what people like, and it’s partly why people don’t like him.

The Untouchables isn’t so bad. But it’s the epitome of cheese. It’s cheese cinema. Cheese fest ‘87. I mean, I guess it’s mostly the music that’s cheesy, the heroic AMERICA music while the heroic police officers get on their steeds and fight the evil gangsters. However, Costner is awesome as usual, and it features another bizarre, shoehorned lifting of a famous movie sequence—the baby carriage scene from Battleship Potempkin.

Did you know Brian De Palma directed the Bruce Springsteen music video where he’s just dancing on stage and then he brings up Courtney Cox for her big break? Yep.

Casualties of War, what a way to end the 80s, with a devastatingly under-seen, underappreciated whimper. I suspect this is one of those times where by virtue of bad luck, the director was working against the popular grain. Like how John Carpenter got fucked over timing wise when he made Starman and The Thing, both not cared about at the time of their release because the former featured good aliens when audiences wanted aliens to be bad, and the latter, vice versa. Casualties of War features some of the best performances that nobody has ever seen from Sean Penn, a young John C. Reilly, and of course, Michael J. Fox. It echoes war classics like Kubrick’s Paths of Glory and is actually a great, depressing, gut-wrenching movie. Also it has a bizarre, intellectualized ending.

Now we’re in the 1990s.

It’s been said that when they were younger, Steven Spielberg looked up to De Palma. They were friends but De Palma was a dashing, learned, intellectual from New York. He was large and imposing, yet warm and inward. De Palma had already been making movies for almost ten years when Spielberg was trying to make it as a hot shot kid lying about his age to appear younger. By 1996 however, the tables had turned. While De Palma was suffering through Hitchcock comparisons, controversial violence, accusations of sexism, and mega box office flops, Spielberg was busy making the most popular, successful, and iconic movies of all time. David Koepp, who had just adapted Jurassic Park for Spielberg, next teamed up with De Palma to adapt Carlito’s Way, De Palmas best movie. (I already covered it earlier.)

De Palma spent his career chasing box office success while not compromising his artistic vision. But while Spielberg did the same, it turned out that his vision aligned with the public, and thus made him the most household of all the household name directors. (When a Spielberg movie goes iconic, credit is given to him. When it happens to De Palma, he has rappers restoring his movie or talking about what a great first book Stephen King wrote. It’s a shame.)

De Palma struggled as a writer/director, and failed even more miserably as a director for hire with Bonfire of the Vanities a famous flop starring Tom Hanks and Bruce Willis. (It opens with a beautiful long take and actually there are some neat things in it, but ultimately it is unwieldy and over the top.) And by 1996, it looked as though De Palma was done—not in a literal sense, but just in that he had tried it all and failed.

It was then that Spielberg gave him the opportunity to direct Mission Impossible. The movie is really worth two shots, plus that one scene we all remember that I talked about earlier. The two shots being some dutch coverage that look awesome, somewhere before a bunch of water explodes. However, with Mission Impossible, De Palma finally didn’t drop the ball. It’s his highest grossing movie and a bonafide blockbuster that spawned a franchise (albeit a shitty one).

Snake Eyes was also co-written by Koepp and De Palma, and is actually pretty good. It’s basically just a noir thriller. It opens with an awe inspiring long take that nobody will ever care about because it’s in Snake Eyes and not Goodfellas, Boogie Nights or Touch of Evil. When De Palma does it, it’s not ‘cool’, apparently. Anyway, Gary Sinise is awesome in it and it’s got great lighting.

Fuck Man, Mission to Mars. I mean, what? Fuck. God that movie sucks.

Femme Fatale is De Palma’s most interesting movie, and his most beautiful. It’s the only transcendent script he ever wrote, and its weirdness once again reaches Lynchian proportions. The movie plays out like an exotic dream, and it might be. The opening is perhaps one of the most detailed, brilliant sequences in movie history, with multiple layers all intercut. It’s really a cinematic ballet unfolding masterfully by someone who had amassed 40 years of filmic knowledge and is putting it all to good use. The movie itself homages all types of old movies, and does so in such an abstract and refreshing way that you can’t help but become completely immersed. It’s an amazing thing when an artist has been working that long and not lost touch with his own sensibility, and can still execute not only at the highest level, but still create something ‘different’. Femme Fatale might be the last great De Palma movie.

I’ve skipped a few along the way. Raising Cain, a visual masterpiece with some scary moments and a crazy ass performance by Lithgow that’s totally worth the price of admission. But ultimately, it’s just a Lifetime movie but weirder. The pale, pinkish hue is my favorite part.

The Black Dahlia sucks because of Josh Hartnett and the fact that it’s long and confusing.

Finally we arrive at Redacted. A movie so out of touch and misplaced it doesn’t even seem real. Redacted is De Palma doing what he used to do in the 60s. But 40 years later he’s lost his zest, fun, and brain. De Palma said that with the state of politics in America in the mid 2000s, he was surprised that there weren’t a ton more anti-war films being made. And he’s right. He was also remembering back to 40 years ago when they had the Vietnam war and people like him made, edgy, cool, subversive anti-war movies like Greetings. I respect the fact that he then went out and made one. Redacted is what he said people should be doing. And, perhaps ironically, it is as bad as you’d expect the people of today to make. In fact it’s bad in all the worst modern ways: horrible acting by non-actors trying to come off as ‘real’ in some shitty-looking fake YouTube internet nonsense, and unconvincing surveillance footage.

What’s weird is that 40 years ago he did it so well. The scene in Hi, Mom!, the Be Black Baby scene, is so good, and represents reality so well. What happened? I think what happened is he’s no longer in his late twenties, worrying about getting laid and not taking himself so seriously. By the 2000s, in his 60s, he is taking himself way seriously, which actually undermines the entire message. Part of the message, subtext, and charm of a movie like Greetings is that it is silly. But its silliness is a slap in the face of convention. A slap in the face of organization, homogenization, media, and society. It’s what makes it subversive, and you really get a sense of the people making it. This all becomes circular, and you end up with something interesting by way of itself. Redacted, however, feels out of touch. Because it is. Because it’s not the kind of thing De Palma does well.

The filmography of Brian De Palma is a subversive wonderland. A sexually-charged nightmare where villains are sinister and heroes are accompanied by larger than life scores that make sure you know they’re the good guys. The De Palma-verse is populated by cinematic experimentation, unrivaled by his contemporaries and successors. It’s a world where split diopter lenses show us the murderer’s knife lurking in the background, and split screens put us on the edge of our seats. It’s where long takes and fast cutting intersect in the hands of someone who marvels at the possibilities of the movies. Few directors delight in the ability of movies to shock us and scare us and tap into our primate senses that something dark is waiting to get us like De Palma does.

To forget De Palma is to forget that art is meant to entertain and that those who utilize cinematic tools to do so are the most transcendent, not the most trivial. Even if those tools often result in a disjointed mess. I’d rather watch a failed attempt than a completed empty gesture.

I’m looking forward to seeing Passion. A lesbian sex thriller starring Rachel McAdams? Don’t mind if I do.

I read this whole thing. cool!

Passion is a remake and a total failure!

I disagree with your point where you say that Obsession was the first ‘ blatant’ Hitchcock movie of Palma. Sisters (1973) was. It had the sure touches of Rear-Window. Plus the long time music collaborator of Hitchcock as its composer. But what seemed most interesting to be, about sisters, was that the film begins with a scene of voyeurism, which ultimately became a strong recurring theme and plot drivers in most of his thrillers. And it wasn’t always a character in the movie. Very often we audience took to the role guided by De Palma’s voyeuristic camera. For me it was Sisters which marked the arrival of the De Palma more than any other movie.

I like what you’ve said here and I partly agree. I find Sisters to be a little, for lack of a better word, weirder and unpolished to be as much of a Hitchcock homage. Sisters, to me, feels like a wacky, avant garde thriller with touches of Hitchcock. I think the classy gloss of Obsession is where he hit his Hitchcock stride.